Minnesota Needs a Balanced Approach to Solving Deficits

Minnesota faces a weak economy, daunting state deficits and some very tough choices. The February economic forecast showed the state has a new $1 billion budget shortfall in the current FY 2010-11 biennium and a $7 billion deficit for the FY 2012-13 biennium, when the impact of inflation is included.[1]

It is essential that Minnesota take a balanced approach to solving its budget shortfalls, including raising revenues, which would enable the state to maintain core state investments in education, health care, job training and other services that help Minnesotans weather these tough times and position the state for when prosperity returns.

Policymakers also have the opportunity to reverse the trend of rising regressivity in Minnesota’s tax system, which has shifted more of the responsibility for funding state and local services on to low- and middle-income Minnesotans.

As policymakers consider reforms to the state’s tax system, they are doing so in a context where Minnesota’s tax system is a smaller share of the state’s economy than a decade ago. The average share of income that Minnesotans pay in state and local taxes dropped by 13 percent from 1996 to 2006.[2] This decline should come as no surprise, considering that Minnesota made the largest tax cuts in the country in 1997, 1999 and 2001.[3]

Minnesota faces this budget deficit with a considerably less fair tax system than in the previous decade. In particular, the wealthiest one percent of Minnesota households — those with incomes over $448,000 — paid 8.9 percent of their incomes in taxes in 2006, compared to the statewide average of 11.2 percent.[4]

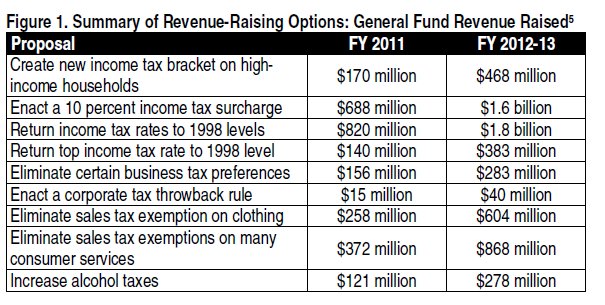

This analysis does not endorse any particular proposal, but presents a number of possible proposals — many of which have been discussed by the legislature in recent years — that could be part of a revenue-raising package. The analysis below assesses how much revenue each proposal would raise and its impact on tax fairness.

Income Tax Changes

The income tax is the state tax that relates the most to the ability to pay. Recent proposals to increase the income tax would increase the degree of fairness of Minnesota’s state and local tax system. These proposals include:

- Creating a new upper income tax bracket for high-income Minnesotans

- Enacting an income tax surcharge

- Returning income tax rates to 1998 levels

There have been several proposals to create a new income tax bracket for high-income Minnesotans. They are referred to as “fourth tier” proposals, as they add a new income tax bracket on top of the state’s three existing brackets.

In the 2009 Legislative Session, the legislature passed a new 9.0 percent bracket for taxable income over $250,000 for a married couple.[6] Were the state to pass such a proposal today, it would raise $170 million in FY 2011, about 17 percent of the current $1 billion budget deficit, and $468 million in the next biennium.[7]

Some have raised concerns about the potential impact that a fourth tier income tax would have on small business owners. A Minnesota Department of Revenue analysis found that only 5.7 percent of households with small business income would pay any additional taxes because of the proposed new bracket in 2009.[8]

A second possible approach to raise revenue through the income tax is to institute an income tax surcharge. This is a fairly simple way to raise revenue: income taxes are calculated following the existing tax laws, but then an additional surcharge is added. A surcharge could also be removed, or “blinked off”, when the additional revenue is no longer needed. The state last used a surcharge to address deficits in the early 1980s.

A 10 percent income tax surcharge would raise $688 million in FY 2011, or nearly 70 percent of the current FY 2010-11 budget deficit. It would raise $1.6 billion in FY 2012-13.[9]

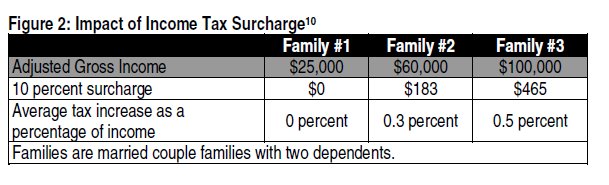

Minnesota’s income tax is based on ability to pay, and so is an income tax surcharge. As shown in Figure 2, high-income households would see larger tax increases, while the impact on low- to moderate-income Minnesotans would be relatively modest or even zero.

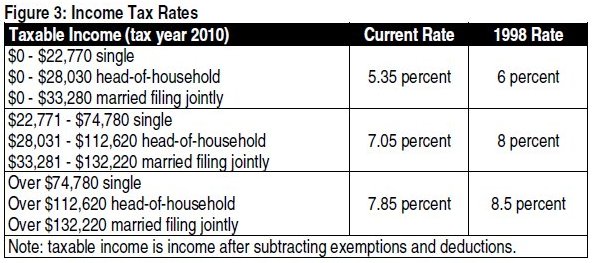

In 2009, the Senate omnibus tax bill rolled back the state’s income tax rates to their 1998 levels, prior to cuts passed in the 1999 and 2000 Legislative Sessions. This option would raise approximately $820 million in FY 2011 and $1.8 billion in FY 2012-13.[11] Figure 3 compares current rates to 1998 rates.

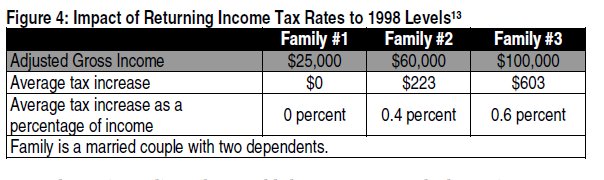

Figure 4 shows how a rollback proposal would affect example households. A married couple with two children and an adjusted gross income of $25,000 could expect to see no tax increase. That same family with an adjusted gross income of $100,000 would see a tax increase of $603. In all cases, the average tax increase would be less than one percent of the household’s income.

As an alternative, policymakers could choose to return only the top income tax rate to its 1998 level. This more targeted tax increase would raise $140 million in FY 2011, or 14 percent of the current deficit. In FY 2012-13, it would raise $383 million.[14]

Sales Tax Modernization

Currently, Minnesotans pay sales tax on most goods but pay no sales tax when they purchase most services, even as services have become a larger share of the economy.[15] There has been some discussion of expanding the sales tax base to include more services, but also to some currently exempt goods.

Two of many options for sales tax base broadening are:

- Eliminating the exemption on clothing would raise $258 million in FY 2011, or 26 percent of the current deficit, and $604 million in FY 2012-13.[16]

- Eliminating exemptions on consumer purchases of many services would raise $372 million in FY 2011 (or 37 percent of the current deficit) and $868 million in FY 2012-13.[17]

The first option simply applies the sales tax to one exempt category: clothing. Minnesota is one of five states with a sales tax that exempts all clothing.[18]

The second option takes a different approach and would tax a range of consumer purchases of services, including: car repair, personal care services (such as hair styling and body piercing), legal services, accounting services and funeral services. By focusing on services purchased by consumers, the proposal follows the argument that sales tax should be paid on final consumption, not on business inputs.

Eliminate Certain Business Tax Preferences

In recent years, policymakers have discussed taking a look at tax expenditures across the range of tax types. In the corporate tax area, this discussion has often focused on eliminating tax preferences that provide benefits for only certain kinds of businesses.

A recent example repeals three such provisions and would raise an estimated $156 million in FY 2011, or 16 percent of the deficit, and $283 million in FY 2012-13.[19] These include:

- Closing the loophole that allows companies to assign profits to a subsidiary in “tax haven” countries, thereby shielding it from taxation.

- Ending the current Foreign Royalty exclusion, which exempts from taxation any income from when a multinational receives royalty payments from its foreign subsidiaries.

- Repealing the special tax treatment of Foreign Operating Corporations (FOCs). FOCs are parts of a multinational corporation that are incorporated in the U.S. but at least 80 percent of their income is from foreign sources. This foreign income currently is taxed at an 80 percent discount. The bill would treat this income the same as domestically-produced income.

These provisions are included in House File 3044 and Senate File 2893 introduced this legislative session, and were passed as part of the House of Representatives’ omnibus tax bill in 2009.

An additional policy that Minnesota could adopt is a “throwback rule.” Corporations that sell their products in more than one state must meet a certain threshold of presence in Minnesota before their profits are subject to the state’s corporate income tax. Because of this threshold, some corporate income becomes “nowhere income,” or profit that is not taxed in any of the 50 states.

A throwback rule would allow Minnesota to tax corporate profits of Minnesota-based companies that otherwise would not be taxed in any state. Sales made to a state in which a corporation is not taxed would be treated as if they were made to customers in Minnesota. Of the 45 states with corporate income taxes, 25 have a throwback rule. Were Minnesota to adopt a throwback rule, it would raise an estimated $15 million in FY 2011 and $40 million in FY 2012-13.[21]

Increase Alcohol Taxes

The 2009 omnibus tax bill approved by the Minnesota Legislature included increased taxes on alcoholic beverages. Implementing that proposal today would raise an estimated $121 million in FY 2011, approximately 12 percent of the current budget deficit, and $278 million in the FY 2012-13 biennium.[22]

Minnesota has two alcohol taxes: an excise tax on manufacturers and wholesalers and a gross receipts tax for retail sales, both on-sale and off-sale purchases.[23] The 2009 legislation included a proposed increase in the gross receipts tax paid on alcoholic beverages at the retail level from 2.5 percent to 5.0 percent, and increasing the alcoholic beverage excise tax by about two cents a drink for beer and wine and about three cents a drink for distilled spirits. (This legislation was vetoed by the Governor and was not enacted into law.)

Alcoholic beverage excise taxes are set at a certain number of cents per unit. In this way they differ from the general sales tax, which is a percentage of the sales price. As a result, alcohol excise taxes do not automatically increase as prices rise with inflation. Alcoholic beverage excise tax rates have not been raised since 1987.[24] Some have advocated alcohol tax increases as an “impact fee,” because of the health and public safety costs the state pays for alcohol abuse.

Creating a Balanced Package can Ensure that Revenue-Raising also Addresses Tax Fairness

Whatever revenue increases are chosen, policymakers should pay attention to tax fairness. The cuts in the progressive income tax at the end of the 1990s, combined with economic trends and more recent increases in regressive property, tobacco and sales taxes, have led to a less fair tax system in Minnesota.

Most state and local taxes are regressive, with the income tax being the major exception. That does not mean that all regressive taxes should be off the table. Instead, the focus should be on creating a package of revenue-raisers that overall improves tax fairness. Strategies to ensure a fair revenue-raising package include:

- Ensuring that a fair income tax increase is part of the overall tax package, and that it is large enough so that the total tax package is not regressive.

- Expanding and maintaining existing refundable tax credits for low-income families, such as the Working Family Credit or Property Tax Refund, or creating new tax refunds or credits that target assistance based on income. If significant expansion of the sales tax is considered, another option would be to create an automatic sales tax credit, similar to the sales tax rebate used during the surplus years, but targeted to specific income groups.

Minnesota Should Take a Balanced Approach to Our Budget Shortfalls

The economy is in a tenuous recovery and the state budget faces huge shortfalls. Minnesota policymakers will need to use a balanced approach and draw on all of the tools in their budget-balancing toolbox to fix our long-term deficits.

It makes sense to use revenue increases as part of the budget deficit solution. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz and Office of Management and Budget director Peter Orszag have written that state spending cuts can hurt the economy more during an economic downturn than tax increases.[25] When government spending is cut, money is taken out of the state’s economy. The state spends less on employee wages and the purchase of goods and services.

In contrast, a tax increase on high-income households is likely to create less economic drag. Residents who are better off are likely to maintain their spending and compensate by saving less. Thus tax increases are a reasonable part of the response to a large state budget deficit.

A balanced approach to solving the deficit – one that includes increases in revenues – would enable the state to maintain the vital services that are critical for the long-term health of our communities and our state. This is the approach that a majority of states have taken to respond to the budget challenges created by the economic crisis.[26]

The economic crisis also provides policymakers with an opportunity to reverse the trend of rising regressivity.

[1] Minnesota Management and Budget, February 2010 Economic Forecast.

[2] Minnesota Budget Project analysis of Minnesota Department of Revenue, 2009 Minnesota Tax Incidence Study, March 2009.

[3] National Conference of State Legislatures, measured as a percentage of the previous year’s collections.

[4] As of 2006, the latest date for which data is available. Minnesota Department of Revenue, 2009 Minnesota Tax Incidence Study.

[5] Income tax estimates are from House Research based on the February 2010 Economic Forecast. All assume that for tax year 2010 the rates are set halfway between current law and their full level. Other revenue estimates are based on fiscal notes and analysis prepared by the Minnesota Department of Revenue, or from the Minnesota Department of Revenue’s Tax Expenditure Budget: Fiscal Years 2010-2013. Sales tax and alcohol tax estimates assume a July 1, 2010 effective date, which results in 11 months of collections in FY 2011. Fiscal estimates done by the Minnesota Department of Revenue on proposals similar to those in this analysis may differ because they will be based on a more complete tax model and/or more current data.

[6] House File 885 (2009 Legislative Session). See also Minnesota Budget Project, Tax Changes in the 2009 Legislative Session: Proposals, Vetoes and Unallotments, October 2009.

[7] Minnesota House Research.

[8] Minnesota Department of Revenue. See also Minnesota Budget Project, Few Small Business Owners Would be Impacted by Income Tax Increases on High-Income Households, May 2009.

[9] Minnesota House Research. Estimate assumes a July 2010 implementation date, a 5.0 percent income tax surcharge in place for the second half of the 2010 tax year, and a 10.0 percent income tax surcharge in place for tax years 2011 and 2012.

[10] Minnesota House Research. Figures shown are the impact once fully phased in. Assumes Family #1 takes the standard deduction, Families #2 and #3 take itemized deductions equal to a percentage of income typical for their income level and filing status, as estimated by the Department of Revenue. Examples do not include any tax credits, such as the Working Family Credit, for which the families may qualify.

[11] Minnesota House Research.

[12] Income tax brackets are normally adjusted each year for inflation. This proposal would not roll back the size of the brackets to where they were in 1998, but would keep them the same as under current law. This proposal assumes a 7.0 percent AMT tax rate.

[13] Minnesota House Research. Figures shown are the impact once fully phased in. Assumes Family #1 takes the standard deduction, Families #2 and #3 take itemized deductions equal to a percentage of income typical for their income level and filing status, as estimated by the Department of Revenue. Examples do not include any tax credits, such as the Working Family Credit, for which the families may qualify.

[14] Minnesota House Research.

[15] Services already subject to the sales tax include, but are not limited to, serving and preparing meals, parking, laundry and dry cleaning, pet grooming, lawn and garden services and most telecommunication services. Minnesota Department of Revenue, Tax Expenditure Budget: Fiscal Years 2010-2013.

[16] Minnesota Department of Revenue, Analysis of S.F. 2980, March 15, 2010.

[17] Tax Expenditure Budget: Fiscal Years 2010-2013. The FY 2011 figure has been adjusted to reflect 11 months of sales tax receipts in the first year of implementation.

[18] CCH 2010 Multistate Corporate Tax Guide.

[19] Minnesota Department of Revenue, Analysis of H.F. 3044, April 2010.

[20] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Closing Three Common Corporate Income Tax Loopholes Could Raise Additional Revenues for Many States, November 2003.

[21] Tax Expenditure Budget: Fiscal Years 2010-2013.

[22] Unofficial and preliminary estimate from House Fiscal Analysis, based on the February 2010 forecast.

[23] House Research, Short Subject: Alcoholic Beverage Taxes, January 2009.

[24] Short Subject: Alcoholic Beverage Taxes.

[25] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Budget Cuts or Tax Increases at the State Level: Which is Preferable During a Recession?, January 2009.

[26] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State Tax Changes in Response to the Recession, March 2010.