The United States has made progress toward recovery from the hardships caused by the pandemic, thanks in part to strong policy action; however, many are still struggling to meet their basic needs. Data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse survey[1] reveal that, while the worst of the recession appears to be behind us, too many in our country are facing continued hardship. The burden falls most on lower-income people and particularly on people of color, who benefitted the least from the economic boom times, and who disproportionately work in industries that were hit the hardest and have been the slowest to recover.

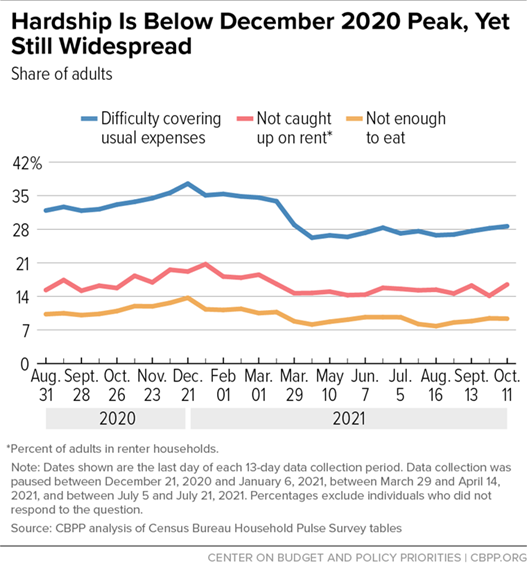

Nationally, rates of hunger, trouble making rent payments, difficulty covering expenses, and unemployment have all lessened since the beginning of the pandemic and have fallen since their peak in December 2020, but many Americans still face economic insecurity.

In Minnesota, we see a similar pattern. The number of our neighbors experiencing hardship has eased somewhat from the worst of the pandemic but remains unacceptably high. This fall, it was still the case that 198,000 Minnesota adults didn’t have enough to eat, 115,000 were behind on rent, and 651,000 struggled to meet basic expenses.

Bold policy responses at multiple levels of government are needed so that all of us can be healthy, safe, and can make ends meet. Our response must target lower-income folks and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities, who were disproportionately harmed by the pandemic and recession and who have long seen their opportunities limited by lack of public investment.

Pandemic-related actions to strengthen the impact and reach of social insurance policies such as economic stimulus payments, unemployment insurance, refundable tax credits for lower-income workers and families, nutrition, and housing subsidies kept or lifted millions of people in the U.S. out of poverty.[2] These actions have lessened the suffering the pandemic and recession brought to so many and put the country on a stronger path to economic recovery. Still, far too many households face instability and there is more work to be done. All Minnesotans should have enough to eat, a secure place to call home, and financial resources to make ends meet.

More people are relying on the safety net to combat hunger

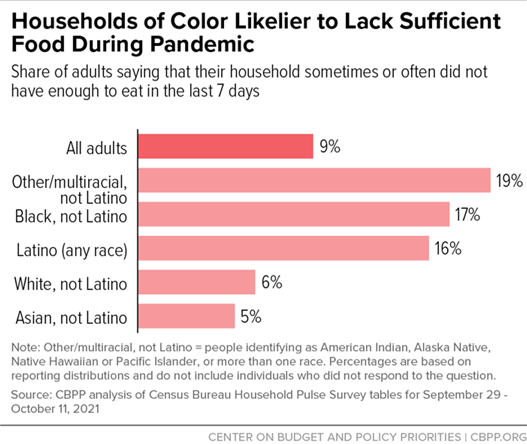

Healthy, nutritious food is vital to staying alive, as well as having the energy to go to work or succeed in school, but not all Minnesotans are able to consistently get the food they need. During October 2021, an estimated 198,000 Minnesotan adults lived in households that sometimes or often didn’t get enough to eat. Nationally, Black, Latino, as well as American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial households taken together were all more than twice as likely to face food insecurity as white or Asian households.[3]

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) helps low-income Minnesotans who are struggling to get enough healthy food to eat. For many, affording the food they need is a challenge at the best of times, and the pandemic increased the number of people needing food assistance. In July 2021, 452,500 Minnesotans participated in SNAP, which is 4 percent higher than in July 2020 and almost 16 percent higher than in February 2020, before the pandemic hit.[4]

Pandemic-related legislation provided temporary increases to SNAP benefits through emergency allotments in March 2020. In addition, the federal COVID-19 relief package passed in December 2020 temporarily increased SNAP benefits by an additional 15 percent. While the pandemic-related increases have ended, a new permanent improvement in the underlying calculations means that the monthly benefit amount has increased by $36 per person when compared to what it would have been without the change in calculations.[5]

In addition, federal policymakers temporarily expanded the school lunch program through Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT), which provided funds for eligible children to purchase food.[6] Other measures to combat hunger included increasing reimbursement rates per meal so schools could purchase more nutritious food, and giving schools the option to provide free meals to all students.[7] Continued policy action to build on these successes is important for ensuring that all Minnesotans can grow and thrive.

Many are behind on rent and facing eviction

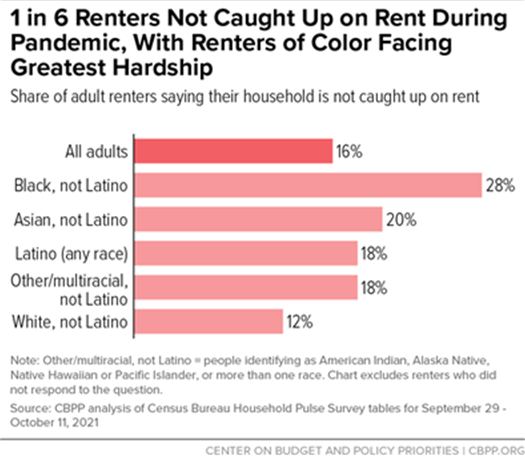

While the number of people behind on their rent payments has fallen since December 2020,16 percent of renter households in the U.S. are still not caught up on rent, including a higher percentage of BIPOC renters. The percentage of Black renter households behind on rent is over twice that of white renter households. Approximately 1 in 5 Latino renter households, Asian renter households, and American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial renter households taken together are not caught up on rent. In Minnesota, 12 percent of adults in rental housing, or nearly 115,000 people, are not caught up on rent.

This housing crisis is not uniquely created by the pandemic; the number of households struggling to afford rent has been increasing for decades. When accounting for inflation, rents in Minnesota increased 7 percent from 2001 to 2018 while renters’ wages failed to keep up. Rent takes up a huge amount of household income for many folks: 141,800 Minnesota households spent over half of their incomes on rent in 2018.[8]

The number of households behind on rent is increasingly worrisome and we could see greater homelessness, given the lifting of eviction moratoriums in Minnesota between June 30 and October 12, 2021. Renters who haven’t applied for or don’t qualify for pandemic-related rental assistance can now be evicted for non-payment of rent.[9] Of U.S. renters who are behind on rent, 45 percent (an estimated 3.6 million adults) reported that they were somewhat or very likely to be evicted in the next two months. Of renters who were behind on rent, households with children were more likely to report that they faced eviction than households without children (50 percent vs 39 percent, respectively).

In addition to ensuring renters can receive rental assistance to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, policymakers at the state and federal levels must increase investments in affordable housing to tackle the long-standing affordable housing shortage and ensure that lower-income households have safe, secure housing that meets their needs.

Unemployment rates improve but job recovery is slower for low-wage industries

Unemployment is another realm where the burden is falling hardest on those with the least financial cushion. Although the economy has added back many jobs since the beginning of the pandemic, low-wage jobs — which are disproportionately held by BIPOC workers and women — are still far behind. A legacy of structural racism including unequal educational opportunities means that workers of color are more likely than white workers to hold low-wage jobs. The national unemployment rates by race continually show that Black and Latino workers are much more likely to be out of work than white workers.[10]

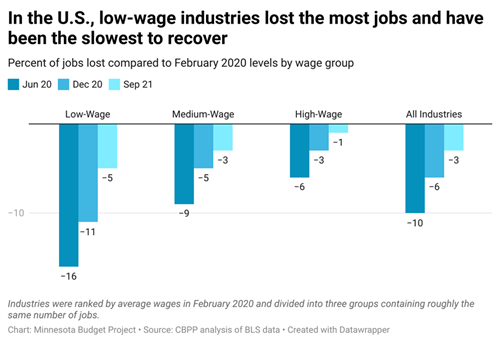

In the beginning of the pandemic, sharp declines in the number of jobs in the U.S. occurred when uncertainty, illness, and public health measures shut down many businesses, but low-wage industries were hit the hardest. In June 2020, the number of jobs had decreased by 10 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels in February 2020. The job loss varied by industry, with low-wage industries such as hospitality and child care losing 16 percent of jobs, compared to 9 percent of medium-wage jobs and 6 percent of high-wage jobs.

While the number of jobs is improving, as of September 2021 we still see the largest job losses in the lowest-wage industries. Across all industries, there are 3 percent fewer jobs than in February 2020. Low-wage industries still lag pre-pandemic levels by 5 percent, medium-wage industries by 3 percent, and high-wage industries have almost fully recovered at less than 1 percent.[11]

Between February 2020 and June 2020, low-wage industries lost over three times as many jobs as high-wage industries, and their recovery has been slower. Not only were low-wage industries particularly hard hit, but the lowest wage jobs in other industries declined at a higher rate as well. Further, workers earning low wages were also more likely to have their hours reduced, potentially costing them important employment-based benefits like health insurance.[12]

During the beginning of the pandemic, the federal CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act made multiple temporary improvements to unemployment insurance. It increased the number of weeks that jobless workers could receive unemployment benefits, made more workers eligible, and provided an additional $600 per week in benefits until July 31, 2020. Other federal legislation passed in December 2020 and the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in March 2021 continued the extended eligibility but reduced the weekly additional benefit to $300 through September 6, 2021.

These swift and bold policy actions kept workers and their families afloat and lessened the pandemic’s damage to the economy as a whole. But unfortunately, millions of unemployed workers lost their UI benefits in September when these improvements expired, exacerbating existing hardships and creating new ones.

The nation’s unemployment insurance system failed to meet the needs of jobless workers before the pandemic and has allowed wide variations among states. Changes made in response to the pandemic were a move in the right direction, and policymakers should take the lessons learned to build a stronger UI system that better meets the needs of today’s workforce, especially low-income and BIPOC workers.

Many still have trouble meeting basic expenses

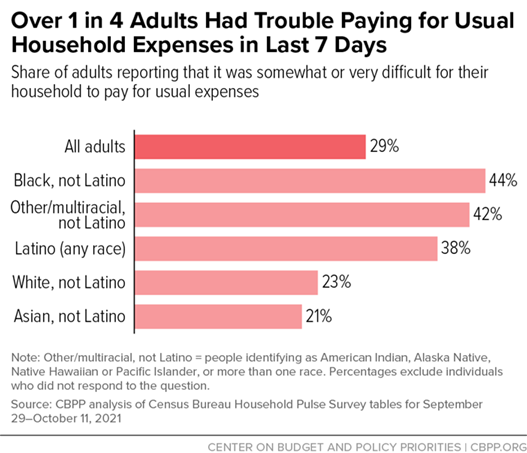

In addition to food and rent, the pandemic made it increasingly difficult for many to afford necessities such as clothing and utilities. During October 2021, an estimated 29 percent, or nearly 63 million adults in the U.S., lacked the funds to cover their usual household expenses. This represents a large improvement since December 2020, when 38 percent of adults had trouble meeting their usual expenses. But that still means nearly 3 in 10 Americans are struggling to afford the basics. Minnesota has fared better, but 17 percent of Minnesotan adults report having trouble paying for usual expenses.

BIPOC households — which tend to have less wealth and savings to fall back on,[13] are more likely to work in lower wage jobs and face higher unemployment rates — were more likely to have difficulty covering their usual expenses. In October 2021 in the U.S., an estimated 44 percent of Black adults, 42 percent of American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial adults taken together, and 38 percent of Latino adults found it somewhat or very difficult to meet their usual expenses.

U.S. households with children also reported higher rates of difficulty covering their usual expenses than adults who did not live in households with children (36 percent versus 24 percent, respectively).

The expansion of the federal Child Tax Credit has made a meaningful difference for struggling families. Federal policymakers increased the amount families can receive, reached more families, and for the first time, allowed families to receive some of their credit in monthly payments, rather than wait until they file their income taxes next year. The monthly Child Tax Credit payments, which began on July 15, 2021, have helped families pay for their basic needs, such as food, rent, clothing, or utilities.[14] In all, the Child Tax Credit expansion is expected to reduce child poverty in the U.S. by an estimated 40 percent.[15]

Continuing policy action is necessary for a robust and equitable recovery

Federal COVID response and recovery legislation, such as the CARES and ARP acts, has helped millions get through the pandemic, but the difficulties faced by lower-income and BIPOC households remain unacceptably high. The health and economic effects of the pandemic will be with us for months or years to come. The danger at this point is not that policymakers will take too much action, but rather that they will do too little and allow us to return to an unacceptable status quo. The result would be continued hardship, deepening racial and income inequality, and a weaker, inequitable recovery.

By Becca O’Donnell

[1] Except where noted, data in this report come from Week 39 of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, which lasted from September 29 to October 11, 2021, and the CBPP’s Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships, November 2021.

[2] Economic Policy Institute, Social insurance programs cushioned the blow of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, September 2021.

[3] The census data do not disaggregate further by race and do not distinguish between subgroups within populations. As a result, the data do not tell the complex story of our nation.

[4] U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, SNAP Data Tables, December 2021.

[5] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Thrifty Food Plan Re-evaluation Puts Nutrition in Reach for SNAP Participants, August 2021. The $36 increase is the difference between the projected benefit with the increase ($169) and the projected benefit without the increase ($133) for one person per month in FY 2022.

[6] U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, State Guidance on Coronavirus P-EBT, November 2021.

[7] Minnesota Department of Education, Seamless Summer Option School Year 2021-22, 2021.

[8] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Minnesota Federal Rental Assistance Fact Sheet, June 2021.

[9] Minnesota Housing, Rent Help MN, 2021.

[10] Economic Policy Institute, State unemployment by race and ethnicity, November 2021.

[11] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data on employment from February 2020 to September 2021.

[12] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, The K-Shaped Recovery: Examining the Diverging Fortunes of Workers in the Recovery from the COVID-19 Pandemic using Business and Household Survey Microdata, July 2021.

[13] Economic Policy Institute, The racial wealth gap: How African-Americans have been shortchanged out of the materials to build wealth, February 2017.

[14] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 9 in 10 Families With Low Incomes Are Using Child Tax Credits to Pay for Necessities, Education, October 2021.

[15] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent, May 2021.