The U.S. economic recovery has been slow. Although Minnesota hasn’t been immune to the effects of an economic recovery characterized by fits and starts, Minnesota’s economy has a number of strengths, compared to the recent past and to national trends. Some economic indicators are back to pre-recession levels, including unemployment. Considering perhaps our most comparable neighbor, Wisconsin, our relative economic strength shines through with Minnesota’s higher labor force participation and higher median wages.

However, the national economy is not seeing the growth in wages and family incomes that we might expect seven years into the economic recovery. As a result, many working Minnesotans are still struggling to reach economic security. The inflation-adjusted wages of many Minnesotans have just gotten back to where they were before the Great Recession hit, but the longer-term trend is that wages aren’t keeping up with the cost of living. As a result, many families can’t meet their basic needs for child care, transportation, housing and health care.[1]

A review of recent economic information reveals that too many working Minnesotans still lack the quality jobs that would allow them to support themselves and their families. We find that:

- Wages for low-wage workers have only just caught up to pre-recession levels, but are still lower than in 2000, when adjusted for the impact of inflation.

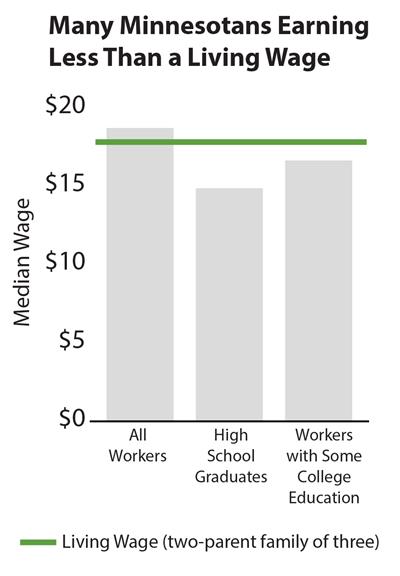

- Many Minnesota workers, including over half of Minnesota workers without a college degree, earn less than what it takes to support a family of three.

- Minnesota’s economic success is not reaching all communities; people of color are more likely than other Minnesotans to be underemployed or unemployed.

State policy choices can play an important role in building a future where all Minnesota workers benefit from the economic growth they help create. Policymakers can ensure that Minnesotans’ hard work pays off and build a strong economic future for us all by improving job quality standards, ensuring Minnesotans can get good jobs, and supporting low-wage workers as they climb into the middle class. Specific steps in this direction include expanding the availability of earned sick time, making child care affordable for more families, boosting incomes through an increased Working Family Tax Credit, and ensuring access to good jobs by making sure driver’s licenses are available to all Minnesotans, regardless of immigration status.

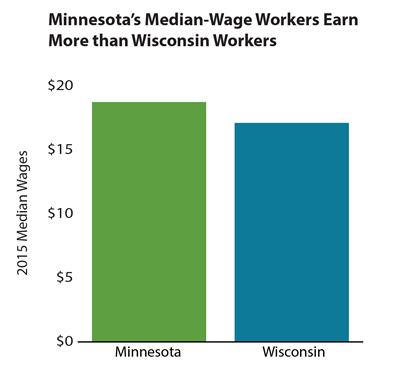

Minnesota Workers Faring Better than Wisconsin Workers

Minnesotans often like to look to their neighbor, Wisconsin, to see how they stack up. And while Wisconsin often has an edge when it comes to football, Minnesota takes home the economic trophy. Minnesota’s workers are in the labor force at higher rates, earn more and are less likely to be unemployed than their counterparts to the east.

Minnesotans value work and that shows in our high percentage of adults in the workforce, at 70.5 percent. This is much higher than the national rate of 62.7 percent. And while Wisconsin also beats the national average, they can’t beat Minnesota. In Wisconsin, it’s estimated that 67.8 percent of adults are in the labor force, about three percentage points lower than in Minnesota.

Workers in Minnesota are also more likely to have jobs. Minnesota’s unemployment rate of 3.8 percent beats the national rate of 5.3 percent, and is much lower than Wisconsin’s 4.6 percent. Additionally, unemployed workers in Minnesota are less likely to be out of a job for six months or more. In Minnesota, 17.5 percent of unemployed persons are “long-term unemployed.” In Wisconsin, that share is 25 percent.

Minnesota workers also earn higher wages than Wisconsin workers. The median wage for Minnesota workers is estimated to be $1.60 an hour higher than for Wisconsin workers, which is more than a 9 percent difference in median wages.

However, while we have economic bragging rights compared to Wisconsin overall, still too many Minnesota workers are experiencing stagnant wages and can’t find the jobs they need to make ends meet.

The Economic Recovery Is Not Yet Bringing Strong Wage Growth

Minnesotans want to work and succeed. However, productivity and wage growth are no longer rising in sync at the national and state levels, which means that the benefits of Minnesota’s economic growth are not reaching all those who contribute to the state’s economic success.

This reflects two national trends: first, since the 1970s, wages no longer rise in tandem with growing productivity; and second, to the extent that productivity growth has brought about growth in wages, that wage growth has primarily gone to high-wage workers. The combined result is relatively stagnant wages for the majority of American workers and an increase in income inequality.

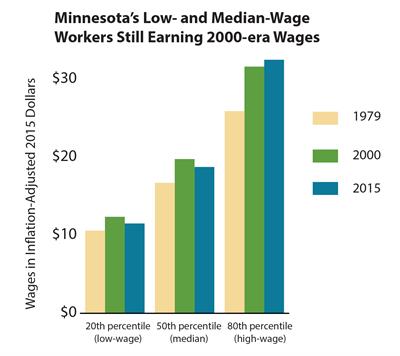

The recession took its toll on wages, and the recovery is not yet resulting in strong wage growth nationally or in Minnesota.[2] Inflation-adjusted wages for low-wage workers have only recently returned to 2007 levels, the year before the Great Recession hit. And wages for low- and median-wage workers are still lower than 2000 levels, the year before the previous recession hit. In fact, in 2015, low- and median-wage workers were earning about 5 to 7 percent less than their 2000 level earnings when inflation is taken into account. High-wage workers are doing better, earning 3 percent more than they did in 2000.[3]

This lack of wage growth for low- and median-wage Minnesota workers has occurred despite rising productivity. Minnesota productivity has increased by 9.5 percent since 2007 and by 22.6 percent since 2000.[4]

This pattern holds over a longer time span. High-wage workers have seen the fastest wage growth, with 25.4 percent wage growth from 1979 to 2015, while median-wage workers’ wages grew by 12.1 percent and low-wage workers’ wages only increased by 8.7 percent, after adjusting for inflation. Again, wage growth has lagged substantially behind productivity growth, as productivity rose by 77.0 percent since 1979.

Not only has the disconnect between wages and productivity meant relatively stagnant wage growth for many, but it has also been a major contributing factor to rising income inequality. The effects of these national trends are clearly seen here in Minnesota. In 1979, the median wage of high-wage workers was 2.4 times higher than the median wage of low-wage workers. That gap has increased, and in 2015, high-wage workers’ wages were almost three times, or nearly $21 an hour, higher than low-wage workers’ wages. Research shows that had the hourly pay of the typical American worker kept track with productivity growth during this time, income inequality would not have risen.[5] The new wealth created in our economy clearly went primarily to the highest earners and did not find its way to many who have worked hard at the bottom and middle of the pay scale.

Many Workers Can’t Afford the Basics

Despite Minnesota’s high labor force participation rate, stagnant wages mean that too many Minnesota families are unable to afford a basic standard of living. The Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development calculates that both parents in a family of three need to earn $17.57 per hour to afford their basic needs.[6] However, there are not enough jobs that pay these wages, especially for workers with lower levels of education. In 2015, more than half of all Minnesotans without a college degree made less than this wage.

This living wage covers a basic needs budget that only includes necessary expenses that Minnesota families face, such as the cost of food, child care, housing and health care. It does not include money for savings, entertainment or vacations. The living wage standard varies across the state, from $12.94 in Stevens County to $19.65 in Isanti County.

Low-wage workers are important to the state’s economy. They work at grocery stores and take care of Minnesota’s children, and they spend their paychecks at local businesses. These workers are integral to our state’s economy, yet today too many of them don’t earn enough to support a family.

People of Color Earn Lower Incomes, Are More Likely to be Unemployed or Underemployed

Minnesota is an above-average state in many ways. We have a high share of residents participating in the labor force, a higher median income than many other states and a lower unemployment rate. However, this disguises the fact that people of color in Minnesota often lack the same opportunities that white Minnesotans enjoy.

People of color make up an ever larger share of our workforce, and our economy should make full use of their skills and abilities. With a tightening labor market and a labor shortage on the horizon, it’s crucial for the state’s economic future that all Minnesotans have the opportunity to reach their fullest potential in the labor market.

However, in Minnesota, people of color are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed than white Minnesotans.[7] In 2015, while Minnesota’s overall unemployment rate was 3.8 percent, the unemployment rate was 14.2 percent for African-Americans. That means that about 1 in 7 African-Americans in the labor force are unable to find work.

Finding a full-time job that properly uses a worker’s skills is an important path to economic security. But this path is less available to workers of color. These workers are more likely to be underemployed, a more comprehensive measure than unemployment that also includes workers who are not able to find the work they need.[8] While overall 1 in 12 Minnesota workers are underemployed, 1 in 10 Hispanic workers and more than 1 in 5 African-American workers are underemployed.

The finding that people of color are more likely to lack full-time work that meets their skills contributes to the fact that people of color generally have lower incomes than white Minnesotans.[9] While the median income for white Minnesota households was $67,000 in 2015, the median income for Hispanic or Latino Minnesota households was only two-thirds of that at $43,400, and black Minnesotan households had incomes less than half the white Minnesotan households’ median income, at $30,300.

Policy Choices Can Expand Access to Good Jobs and Economic Security

Workers need good jobs to meet their basic needs and support their families, but many Minnesota workers are struggling. Without a strong workforce, Minnesota’s future economic success is threatened. Lawmakers should adopt policies so that more Minnesotans can get and keep quality jobs. These include policies that:

- Improve job quality standards;

- Ensure Minnesotans can get the education and training they need, and can get to good jobs that make full use of their skills; and

- Support low-wage workers trying to make ends meet and move into the middle class.

There are specific policy changes well poised to move forward in the 2017 Legislative Session that would result in more Minnesotans having good jobs and economic security. They include:

- Expanding access to earned sick leave;

- Making affordable child care available to more Minnesota families;

- Boosting incomes by increasing the Working Family Tax Credit; and

- Allowing all Minnesotans to qualify for driver’s licenses, regardless of their immigration status.

Expanding access to earned sick leave. More than one million Minnesotans lose wages or even their jobs if they take time off to care for themselves or a loved one. Making earned sick leave available to more workers would help families better make ends meet, can reduce employee turnover, and contribute to healthier and more productive workplaces. Expanding access to earned sick leave would especially reach those who can least afford to lose wages, including low-income workers and people of color. It’s estimated that about 40 percent of workers in Minnesota lack earned sick leave, and the situation is more pronounced among communities of color. Almost half of black workers and 60 percent of Hispanic workers in Minnesota do not have earned sick leave. Expanding access to earned sick leave would also significantly help people with low incomes: 66 percent of Minnesota workers earning less than $15,000 a year lack earned sick leave.[10]

In the absence of state action, local governments have seen momentum on this issue. Earlier this summer, the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul passed new requirements that will allow many additional employees to earn paid sick time.

Making affordable child care available to more Minnesota families. When Minnesota families have affordable child care that fits their needs, parents are able to go to work or school; children can thrive in stable, nurturing settings; and employers have the reliable workers they need. Child care can be one of the largest expenses that families with young children face, and for too many Minnesota families, the cost of child care is out of reach.

Two important strategies toward all Minnesota families being able to afford the child care they need are increasing funding for Basic Sliding Fee Child Care Assistance and a targeted expansion of the state’s Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit for low- and moderate-income families. Currently 6,561 Minnesota families are on waiting lists for Basic Sliding Fee for the assistance they need to afford child care.[11]

Policymakers should also improve the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit by increasing the amount of credit families can receive and making more moderate-income families eligible for the credit. This tax credit helps Minnesota families better afford the high cost of child care, but it hasn’t kept up with the growing cost of care.

Improving the Working Family Tax Credit. The Working Family Tax Credit boosts the incomes of people working at lower wages, enabling them to better support themselves and their families. And its benefits go well beyond that. The Working Family Credit is based on the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which has long-lasting positive effects for children who receive it, including that these children are healthier, do better in school and earn more as adults.[12]

The Working Family Credit also makes the state’s tax system fairer by offsetting a portion of the substantial state and local taxes that lower-income working people pay. A boost in the Working Family Credit is needed, as even with the current credit, low- and moderate-income Minnesota households on average pay a larger share of their incomes in state and local taxes than high-income households.[13]

Important improvements to the Working Family Credit were passed in the 2016 tax bill but not ultimately enacted into law. These provisions would reach 386,000 working families and individuals and:

- Increase the size of the tax credit for most currently eligible families and individuals;

- Make some additional families and individuals eligible by increasing the incomes that they can earn and still qualify for the credit; and

- Reach younger workers without dependent children by lowering the age requirement to qualify for the credit from 25 years old to 21.

This proposal would make economic security within reach for more Minnesotans, regardless of their race or where they live. An estimated 30 percent of Minnesota households eligible for the Working Family Tax Credit are people of color,[14] and 48 percent of households receiving the credit live in Greater Minnesota.[15]

Opening up access to good jobs by allowing Minnesotans to qualify for driver’s licenses without regard to immigration status. Minnesota workers who don’t have driver’s licenses find their job opportunities are limited – there are some jobs they can’t get to, and they can only take shifts when public transportation is available. That’s the situation that about 78,000 Minnesotans in communities across the state are in, because they are unable to get driver’s licenses due to their immigration status.[16] If these Minnesotans could get driver’s licenses, they could more readily fill jobs that match their skills and abilities, which is likely to increase their earnings. This can have a positive ripple effect on the state’s economy as well, as those higher earnings are spent on goods and services in our local communities.

Expanding access to driver’s licenses also helps businesses get the employees they need. With a tightening labor market and large share of the population aging out of the workforce, Minnesota can’t afford to leave qualified workers on the sidelines because they are unable to get to work. It’s also one important step in reducing racial disparities in unemployment and underemployment in Minnesota.

Minnesota Should Support Workers Left Behind to Build an Economy for All

Our state needs a strong workforce to build a vibrant economy. While Minnesota workers are outperforming their peers in Wisconsin, too many Minnesotans are being left out and left behind in the current economic recovery, especially low-wage workers and people of color. Economic growth hasn’t meant an increase in wages and living standards for a majority of workers. And workers of color are often unable to use all of their skills in the workplace.

There is strong momentum at the state and local levels for policies that increase opportunities for Minnesotans to find and keep good jobs and build an economy that works for all. These include city-level expansions in sick leave and the strong, bipartisan support for improving tax credits for families and workers demonstrated in the 2016 Legislative Session. Policymakers must take the opportunity in 2017 to make these policies a statewide reality. Our workers need to succeed for our economy to succeed.

By Clark Biegler

[1] Except where otherwise noted, data in this report come from analysis by the Economic Policy Institute of Current Population Survey and Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Latest figures are from 2015, and all wage calculations are inflation adjusted to 2015.

[2] This report defines low-wage workers as workers in the 20th percentile and high-wage workers as those in the 90th percentile. Median-wage workers are defined as those who earn the median wage, the wage at which 50 percent of workers earn wages below and 50 percent earn above.

[3] This report compares 2015 wages with 1979 and 2000 figures because they compare similar points in the business cycle.

[4] Economic Policy Institute, Understanding the Historic Divergence Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay: Why it Matters and Why it’s Real, September 2015.

[5] Economic Policy Institute, Understanding the Historic Divergence Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay: Why it Matters and Why it’s Real.

[6] Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, Cost of Living in Minnesota, 2015. The typical family is a family of three with one adult working full time and the other working part time.

[7] This analysis focuses on African-American and Hispanic workers of color only because of data limitations. The data source used does not provide information about other communities of color, nor does it allow us to distinguish among subgroups within the Hispanic and African-American communities.

[8] Underemployment includes workers who are unemployed, working part time when they prefer full-time work, and workers who are not in the labor force but are available for work and have searched for a job sometime in the past year.

[9] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2015.

[10] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Access to Paid Sick Time in Minnesota, September 2014.

[11] Minnesota Department of Human Services, Child Care Assistance Program: Number of Families on the Basic Sliding Fee Waiting List, June 2016.

[12] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds, October 2015.

[13] Minnesota Department of Revenue, 2015 Minnesota Tax Incidence Study, March 2015.

[14] This figure represents the estimated share of households eligible for the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, on which the Working Family Tax Credit is based. Brookings analysis of 2013 American Community Survey data.

[15] Greater Minnesota is defined as all those counties not in the 7-county Twin Cities metro area. Minnesota Department of Revenue, Tax Year 2013 Minnesota Income Tax Statistics by County.

[16] Minnesota Budget Project estimate of the number undocumented immigrants in Minnesota who are 16 or older and have not already been approved for DACA.