Inequality of pandemic’s impact can be illustrated by the “K-Shaped” economy

As we put behind us a year for the history books, let’s talk about the economy. While no income group or community has been untouched by the coronavirus, the economic recession it has triggered may be the most unequal in modern history. Underlying economic and racial disparities have been heightened, and are reflected in Americans having increasingly divergent experiences.

Those with the most resources – high net worth, investments, and higher levels of education – have seen increasingly positive gains in 2020. Soaring stock prices and property values have helped increase assets for those who already had the means to possess them. For these Americans, the recovery is well underway. On the other side of the equation, the recession is deep and ongoing: lower-wage workers, people of color, and women have struggled mightily and suffered serious hardships in the midst of record levels of job loss, hunger, and housing instability.

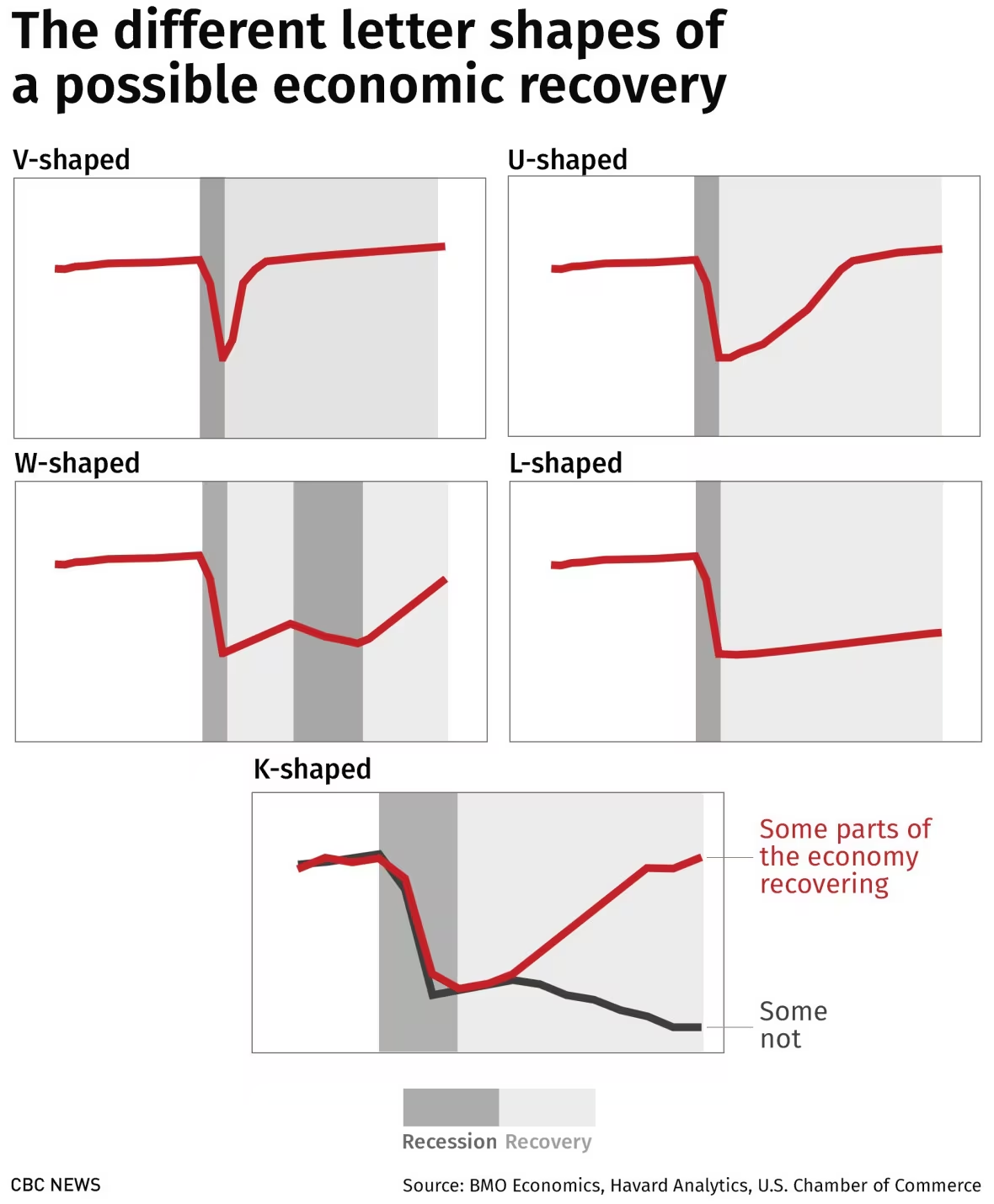

If an economist were to translate these experiences, the resulting graph – showing one segment of the economy on the upswing and the others moving downwards – sort of looks like the letter “K” and is sometimes referred to as “K-shaped recovery.” It looks like this:

This situation calls on policymakers to continue to respond to the recession that so many are still experiencing, and take actions to promote Minnesotans’ health and financial security. It requires raising additional public revenues to fund this response and make investments in a more equitable recovery, including tackling the economic and racial disparities that were already with us, and that the pandemic has spotlighted and made worse.

Jobs and wages are the best indicator of how well everyday people are doing

As the coronavirus pandemic hit and the world shuttered activities, the percentage of the population that was employed dropped to its lowest levels since 1975. By the autumn of 2020, about half of those lost jobs had been recovered, but the rebound is extremely inequitable. [1]

As of October, the United States was still down about 10.7 million jobs compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic, with 7.3 million workers unemployed for four months and 2.4 million workers unemployed for more than six months.[2] Even those who were able to find new jobs may be playing catch-up on rent and essential bills after going without a paycheck for a time.

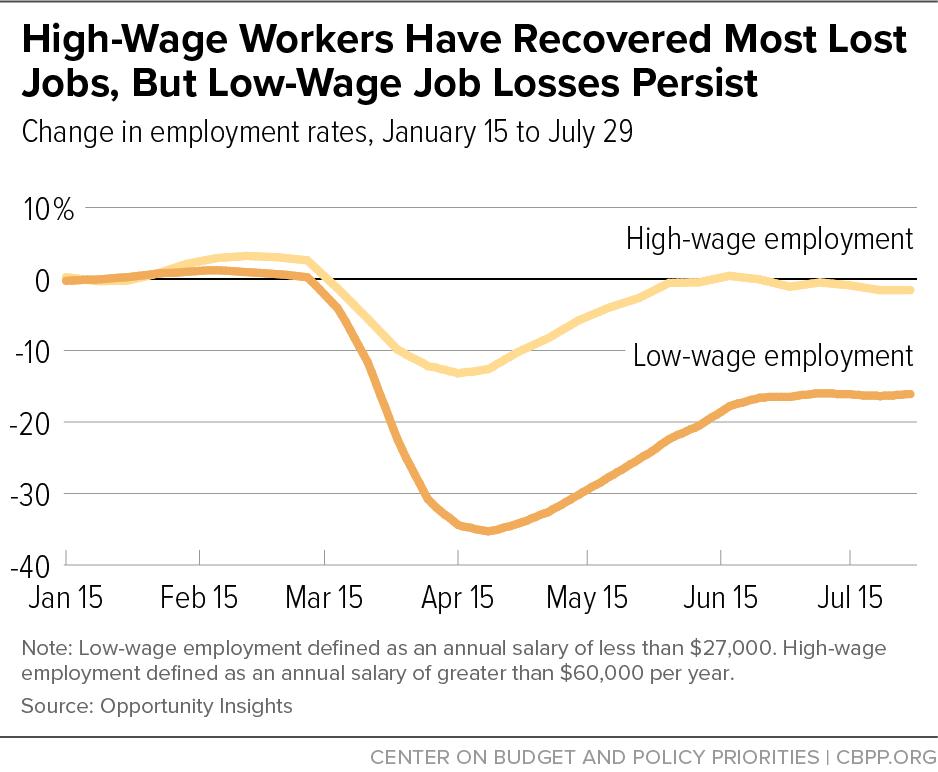

The majority of Americans who lost jobs during the pandemic are in low-wage industries. The lowest-wage industries make up 30 percent of all jobs, but represented 58 percent of jobs lost between February and November 2020. The lowest-wage category of jobs decreased by about twice as much as jobs in more middle-wage industries, and more than three times as much as high wage industry jobs.[3]

Recessions typically harm lower-wage workers more, but the unique nature of the pandemic-driven downturn also plays a large role. The service sector was hit extraordinarily hard, since restaurants, shops, hotels, theme parks, theaters, and many other forms of entertainment and travel had to be closed to stop the virus’ spread.

Due to a legacy of institutional racism that has limited access to education and economic opportunity, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) folks are more likely to experience job loss. People of color are more impacted by changes to the business cycle than white people; the racial gap widens during recessions and shrinks during boom times.[4] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities finds that “indicators of labor-market slack (like unemployment or employment rates) deteriorate faster and further for people of color and, depending on the strength of the recovery, can take longer to make up lost ground.” The graph below illustrates the higher peak levels of job loss among Black and Latinx workers, as well as women.

Additionally, parents – especially mothers – are experiencing significant negative employment impacts due to the pandemic. Unpartnered mothers have left the workforce more than any other parent group.[6] Among Black and Latinx unpartnered moms, the drop in employment is nearly double that of white unpartnered moms. Among all parents, employment has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. Black and Latinx parents experienced a steeper drop in employment compared to white parents. While there are many potential reasons for the profound impact on parents – from lack of work flexibility to the need to supervise their children’s remote learning – the outcome for their families’ well-being is potentially devastating.[7]

Job loss brings additional hardship

Unfortunately, job loss often brings another stress to workers and their families: the loss of health insurance. The Economic Policy Institute projects that since the start of the pandemic, about 6.2 million workers have lost employer-provided health insurance.[8] This presents a huge worry and financial strain on workers and families at a time when access to health care is especially important. Job loss can add paperwork burdens and changes in coverage for people who have affordable health insurance coverage through public programs like MinnesotaCare. Losing access to health care is potentially catastrophic during a pandemic, and stresses about loss of income can exacerbate negative symptoms associated with COVID.[9]

Adding to these challenges: BIPOC Americans are disproportionately dying and facing serious health complications due to COVID.[10] Thus, those most negatively impacted by job losses are also those facing the deepest inequities in health outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased other hardships for millions of Americans.[11] As of December 2020, 13 percent of American adults – 29 million people – reported not having enough food in their household within the last week. One in six American renters were behind on their monthly rent payments. More than one in three American adults had trouble affording basic household expenses. For all of these statistics, Black and Latinx households are more likely to experience hardship compared to white households. While Minnesota’s statistics are slightly better than the national numbers, with 9 percent of adults not having enough food, 15 percent of renters behind on payments, and 29 percent having trouble affording basic household expenses, this still represents hundreds of thousands of Minnesota neighbors suffering extreme hardship.

Higher-income workers, stock market investors not as hard hit initially and are already in the recovery

In contrast, higher-income workers saw less job loss, and high-wage jobs had largely recovered by summer.[12] This in part ties back to the nature of the pandemic. Remote work tends to be more available for workers in jobs that require higher levels of formal education, as they tend to be more computer-based. Instead of being out of a job, these workers were able to change where their work was being done, and by and large continued receiving the same income and employer-provided health insurance.

While these workers still face disruption in their daily lives as a result of the virus, their economic situation may be buoyed by soaring property values, low interest rates that make borrowing cheaper, and rising stock prices that have helped improve their economic situation.

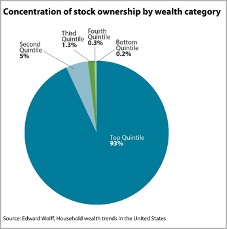

While the media and some political leaders often cite the stock market as a measure of the country’s economic health, it actually has little meaningful impact on most Americans’ daily lives. What it does demonstrate, however, is how much some corporations and those with enough wealth to engage in the stock market are doing, even in a pandemic.

The households that benefit most from gains in the stock market are largely those with the highest incomes: the richest 10 percent of American households own about 84 percent of the value of all stocks owned by American households, and the richest 1 percent own about 40 percent. In contrast, the one-fifth of American households with the lowest wealth owns less than half of one percent of stock value.[13]

There is also a large gap when examining stock ownership by race: 61 percent of white families, regardless of income level, own stocks, with median holdings of $51,400. Among Black families, only 31 percent own any stock, and have much smaller median holdings of $12,000. Among Latinx families, 28 percent have investments in the stock market, with median holdings of $10,800. [14]

Since most folks don’t get much income from the stock market, short-term market gains have little effect on their ability to pay the bills. For most, their connection to the stock market is in the form of a tax-deferred retirement account – meaning the money isn’t actually available to address current financial needs without massive penalties. It’s those who already have high incomes who largely benefit from the stock market’s strong performance.

Early in the coronavirus pandemic, the stock market took such a massive and rapid downturn that circuit breaker provisions meant to force a cool-down temporarily paused trading for short 15-minute periods. But soon, stock values recovered to pre-pandemic levels and beyond. How is this possible when we’re still seeing extraordinary levels of unemployment and crises like homelessness and food insecurity?

The values of securities on the stock market is forward-looking and therefore tends to reflect future optimism, not current realities. Nowhere do we see this better illustrated than April 2020, when 20.5 million American jobs were lost but the S&P 500 stock index put up its best month in 33 years.[15]

Additionally, the stock market tends to emphasize a few very large companies that are not representative of businesses around the country. For example, 20 percent of the market value is comprised of just five giant tech companies: Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet (Google), and Facebook. Internet behemoth Amazon posted a 70 percent increase – that’s a $5.8 billion increase over 2019 – in earnings during the first nine months of 2020, for example, and 80 percent of companies included in the S&P 500 have produced earnings that outpaced analyst estimates.[16] Tech companies, mortgage companies, auto manufacturers, and others have done exceedingly well. (Of course, plenty of large companies, like airlines and some hotel and restaurant chains, have faced significant losses in 2020, reflecting the pandemic’s very unequal impact by sector.)

Policymakers should take action to address current hardships and build a more equitable recovery

It’s clear that the COVID-19 pandemic and recession is profoundly harming the health and economic well-being of many American households. But those with the least resources to get by are getting hit the hardest, while many of those with more resources were less impacted and ended the year doing quite well.

The appropriate government response includes controlling the virus to allow economic activity to safely resume while also promoting health and saving lives, as well as continuing to act to address the ongoing economic hardships that so many are facing.

But we also can’t go “back to normal,” and instead must act to address income and wealth inequality and structural racism. Policy action is needed to deal with the pandemic and jump start the economy, yes – but we also must use this time to build a better, more equitable future. This includes making the investments needed so that all Minnesotans, regardless of who they are or where they live, have what they need to thrive, from good schools and affordable housing, to broadband access and quality health care. Policymakers must also protect public services that Minnesotans count on in the face of state revenue shortfalls.

It will take additional public resources to fund the response to the current crisis and fuel a more equitable recovery. On the state level, Minnesota’s strong budget reserve and other current resources can fund some short-term solutions. Improved taxes on high incomes and wealth are an important tool for states to use as well.[17] This could include expanding income tax rates on the highest-income households, strengthening taxes on capital gains (whose benefits are highly concentrated among the wealthiest households), and increasing estate taxes on inherited wealth. These actions would bring in needed revenues by focusing on those with the greatest ability to pay, and respond to the increased inequities in incomes and wealth brought on by the pandemic.

By Betsy Hammer

[1] Washington Post, The covid-19 recession is the most unequal in modern U.S. history, September 30, 2020.

[2] Economic Policy Institute, Slowdown in jobs added means we could be years away from a full recovery, October 2020.

[3] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships, updated January 2021.

[4] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and The Groundwork Collaborative, The Impact of the COVID19 Recession on the Jobs and Incomes of Persons of Color, June 2020.

[5] Economic Policy Institute, A more comprehensive look at unemployment rates, December 2020.

[6] Pew Research Center, In the pandemic, the share of unpartnered moms at work fell more sharply than among other parents, November 2020.

[7] Pew Research Center, Fewer mothers and fathers in U.S. are working due to COVID-19 downturn; those at work have cut hours, October 2020.

[8] Economic Policy Institute, Health insurance and the COVID-19 shock, August 2020.

[9] N Hertz-Palmor et al, Association among income loss, financial strain and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: evidence from two longitudinal studies, September 2020.

[10] Centers for Disease Control, COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity, November 2020.

[11] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships.

[12] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, High-wage workers have recovered most lost jobs, but low-wage job losses persist, 2020.

[13] Edward N. Wolff, Household wealth trends in the United States, 1962 to 2016: Has middle class wealth recovered?, November 2017.

[14] Pew Research Center, More than half of U.S. households have some investment in the stock market, March 2020.

[15] New York Times, Repeat After Me: The Markets Are Not the Economy, May 2020.

[16] New York Times.

[17] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Improved State Taxes on Wealth, High Incomes Can Help Fuel an Equitable Recovery, December 2020.