Policy choices matter in ensuring that Minnesota’s tax system is fair and raises enough revenue to fund Minnesota’s schools, roads, nursing homes and other critical services. The recent efforts to reach these goals have paid off.

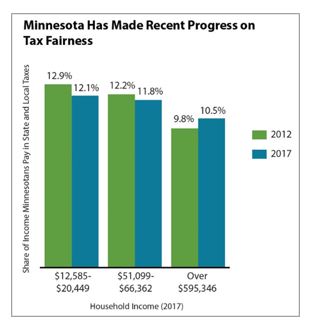

The evidence can be found in the state’s Tax Incidence Study, which looks at all state and local taxes that Minnesotans pay, and measures those taxes as a share of Minnesotans’ incomes. This year’s version of the study has information for 2012 and projections for 2017. This creates a “before and after” picture of what difference the tax reforms of 2013 and 2014 have made.[1] Some of the key findings include:

- The gap between the share of income that the highest-income Minnesotans pay in state and local taxes and what other Minnesotans pay has closed considerably.

- Minnesota’s tax system is still regressive; that means as household income grows, the share of income paid in state and local taxes falls. But the tax system will be significantly less regressive in 2017 than in 2012.

- On average, Minnesota state and local taxes as a share of income will be slightly lower in 2017 than in 2012, and will be 12.3 percent lower than in 1994.

The Gap Narrows, But the Share of Income Paid in Taxes Still Falls as Income Grows

From 1990 to 2012, Minnesota saw a sharp decline in tax fairness.[2] Two factors help explain that trend: rising income inequality and policy choices. Minnesota had come to rely less on state taxes and more on local property taxes, which are based on home value and not as closely linked to taxpayers’ ability to pay. In 2002, local taxes made up 24.6 percent of total state and local taxes in Minnesota. They had increased to 29.7 percent of total Minnesota taxes by 2012.

The 1 percent of Minnesotans with the highest incomes (household incomes over $493,603) paid 9.8 percent of their incomes in total state and local taxes in 2012. This is significantly less than the 12.2 percent paid by a middle-income household making $43,554 to $56,666.

This picture has changed significantly. Minnesota made substantial progress on making the tax system fairer through tax policy changes passed in 2013 and 2014 that, taken together, raised taxes measured as a share of income on the highest-income Minnesotans closer to the state average, and lowered taxes for all other income groups.

While the highest-income Minnesotans still pay a smaller share of their incomes in total state and local taxes than other income groups, the gap between them and other Minnesotans has shrunk. In 2012, the share of their incomes that the 1 percent of Minnesotans with the highest incomes paid in taxes was 1.7 percentage points lower than the state average. In 2017, that difference narrows to 0.9 percentage points.

These outcomes reflect the combined impact of tax changes passed in 2013 and 2014. The 2013 tax reform bill raised additional revenues through creating a new “4th tier” income tax bracket on the 2 percent of Minnesotans with the highest incomes, ending several corporate tax preferences and increasing tobacco taxes. It also included larger property tax refunds for homeowners and renters.

This was followed in 2014 by two tax-cutting bills. These bills increased the Working Family Credit by nearly 25 percent and reduced income taxes through a number of changes that made the Minnesota income tax more aligned with the federal tax code. Policymakers also repealed three sales taxes on business-to-business transactions that had been included in the 2013 tax bill, repealed the gift tax and cut the estate tax.

According to the Tax Incidence Study, the three policy changes that did the most to make taxes less regressive were the 4th tier income tax bracket, increasing the Working Family Credit and larger property tax refunds for homeowners and renters. The two most regressive policy changes were the increase in cigarette and tobacco taxes and estate tax cuts.

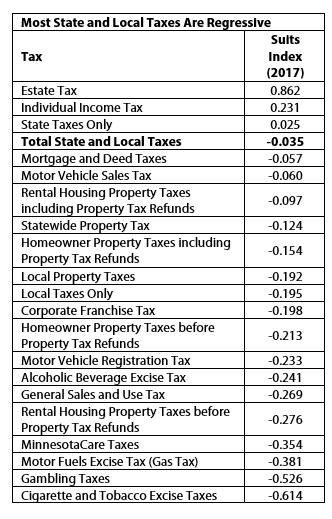

The progress on distributing Minnesota’s taxes more evenly across income groups is also demonstrated through the significant improvement in the Suits Index. The Suits Index is a measure of the degree to which a tax is progressive or regressive. A Suits Index between 0 and +1 means the tax is progressive, and a Suits Index between 0 and -1 is regressive. The Suits Index for Minnesota’s state and local tax system was -0.052 in 2012 but is projected to improve dramatically to -0.035 in 2017.

Notably, while the 2013 tax reform bill increased taxes in order to end a period of frequent budget deficits, taxes are a smaller share of Minnesotans’ household budgets today than in the 1990s. That time period has included tax cuts and tax increases, and ups and downs in income growth, but on average Minnesotans have seen a more than 12 percent drop in the share of their incomes paid in state and local taxes since 1994. In 1994, Minnesotans paid 13.0 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes. By 2012, this figure had fallen to 11.5 percent, and it is expected to drop to 11.4 percent in 2017.

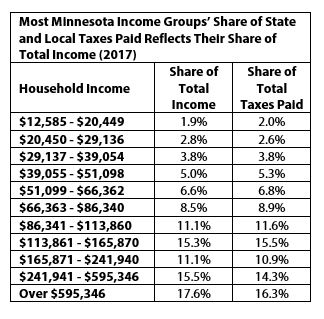

Most Income Groups Pay in Proportion to their Share of Total Income

High-income Minnesotans pay a significant share of all state and local taxes paid in the state. This reflects the fact that these income groups have a large share of all the income earned in the state. However, the share of state and local taxes the highest-income Minnesotans pay is smaller than their share of income.

In 2017, most Minnesota income groups are expected to pay state and local taxes in rough proportion to their share of total income, although many low- and middle-income groups pay more than their proportionate share, and those with incomes above $165,871 pay less. For example, Minnesotans with incomes over $595,346 (the highest-income 1 percent) had 17.6 percent of all income in the state, but paid 16.3 percent of total state and local taxes.

Some Taxes are Distributed More Evenly than Others

Minnesota’s estate tax and individual income tax are the state’s only progressive taxes – meaning that the higher one’s income, the larger the share of income paid for the tax. All other taxes that Minnesotans pay are regressive, where low- and middle-income households pay a higher share of their incomes in those taxes. Gambling taxes and cigarette and tobacco taxes are the most regressive.

Despite the significant progress made in the last two years, Minnesota’s state and local tax system remains regressive overall.

The state’s tax system would be substantially more regressive without refundable income tax credits and property tax refunds. These include the Working Family Credit, the Child and Dependent Care Credit, and the K-12 Education Credit, all of which are part of the state’s income tax system; and the Homestead Credit Refund for homeowners, commonly called the Circuit Breaker, and the Property Tax Refund for renters, also called the Renters’ Credit. For example, absent these credits, Minnesota’s tax system would have a Suits index of -0.075 in 2012, instead of -0.052.

Minnesota Should Stay the Course

Minnesota has made substantial progress in the past few years. Before 2013, Minnesota’s tax system was not meeting our needs. The gap between the share of income that the wealthiest paid in state and local taxes and the share that average Minnesotans paid had grown, and the system was not raising enough revenues to avoid persistent budget deficits.

The cumulative impact of the tax changes passed in 2013 and 2014 was to make Minnesota’s tax system more equitable, and to raise enough revenue to resolve the budget deficit and to fund needed investments in schools, making a college education more affordable, and other building blocks of a prosperous state.

Minnesota’s more positive budget situation today shouldn’t mean a change in direction. More action is still needed to further narrow the gap between the highest-income Minnesotans and all other Minnesotans. In addition, caution must be taken to avoid large tax cuts that would put at risk the state’s ability to sustainably fund critical services. The lesson of the late 1990s and early 2000s is clear: too much tax cutting in the good times was followed by greater reliance on property taxes, double-digit increases in tuition at public colleges and universities, and higher fees. That combination put more of the responsibility for funding public services on to low- and middle-income Minnesotans. Repeating those mistakes would not set a wise course for our state’s future.

By Nan Madden and Clark Biegler

[1] The data in this analysis come from the Minnesota Department of Revenue, 2015 Minnesota Tax Incidence Study, March 2015. It does not include the impact of the small number of tax policy changes passed in the 2015 Legislative Session. The Tax Incidence Study includes over 99 percent of the state and local taxes paid in Minnesota in 2012. The distributional analysis in the study includes the $22.3 billion in taxes ultimately paid by Minnesota residents, or 82.7 percent of the total. The distributional analysis includes estimates of how taxes paid by businesses are shifted to consumers as higher prices, to workers as lower wages and on owners as lower profits. Income includes taxable income as well as nontaxable income such as public assistance, nontaxable interest, and nontaxable Social Security and pension income. A household is defined as “one or two people entitled to file one income tax return or property tax return, plus any dependents.” This definition of a household varies from the Census, which defines a household as all persons who live together in a housing unit. For this reason, the Tax Incidence Study has a larger number of households than the Census, and the median household income is less than reported by the Census. The Tax Incidence Study divides the population into ten groups containing an equal number of households, called deciles. Data concerns regarding the first decile result in the Tax Incidence Study overstating the level of taxation for this group. For this reason, the first decile is not included in graphs and tables in this analysis.

[2] The erosion of fairness is demonstrated by the decline in the Suits Index for Minnesota’s state and local tax system, which was -0.007 in 1990 but was a significantly more regressive -0.045 in 2012. (These figures use a method of calculating the Suits Index using 10 data points, which allows for comparison to past studies. The Suits Indexes used elsewhere in this analysis use the more accurate “full sample” method that uses more than 100,000 data points. The full sample method measures a Suits Index of -0.052 for 2012.)