Prior to the emergence of coronavirus and the public health measures taken to contain it, Minnesota boasted of a strong economy, with low overall unemployment, high workforce participation, and fairly high median income. However, these data points masked the fact that many Minnesotans were facing substantial barriers to accessing good jobs and supporting themselves and their families before the pandemic hit, according to analysis of 2018 data from the Economic Policy Institute.[1]

In particular, workers of color are more likely to face significant barriers to succeeding in the economy. A legacy of discriminatory policies and underinvestment in their communities have left its mark on employment opportunities and wages for Black and Brown Minnesotans.

Minnesotans believe that hard work should pay off, that people who work full time should be able to support their families, and that everyone should have the opportunity to succeed. But slow wage growth and growing income inequality contradicts some of our country’s most deeply held values. Nationally, wages for low- and mid-wage workers have increased only modestly since the late 1970s, and today the highest-income households hold a much higher share of overall income than they did 50 years ago.

These findings underscore that economic growth on its own has not been enough. When workers’ wages don’t keep up, these workers struggle to afford child care, transportation, housing, and health care – the basic building blocks of the standard of living they want to provide for their families. And without these things, people find it even harder to move ahead in the workforce.

The same workers who were already struggling are disproportionately harmed by the coronavirus today. Our policy responses need to prioritize low-income and BIPOC (Black, indigenous, people of color) Minnesotans, and lay the groundwork for a stronger recovery in which economic opportunity is available to all.

High-income earners have benefited most from economic growth

Over the past 40 years, the strongest wage growth has gone to the Minnesotans earning the most, although more recent data shows a reversal of that trend.[2]

The concentration of wage growth at higher incomes is shown by inflation-adjusted wages increasing for high-wage workers by 33 percent, but only by about 20 percent for low- and median-wage workers from 1979 to 2018.

A more positive trend of stronger growth for low-wage workers emerged more recently. From 2017 to 2018, wages for low-wage workers in Minnesota grew by 4.3 percent, or $0.58 per hour. By comparison, wages for high-wage workers went up $1.07, or 3.0 percent. This stronger wage growth for lower-wage workers likely demonstrates how, among other factors, minimum wage increases are boosting workers’ earnings and starting to narrow the gap between their wages and what it takes to make ends meet.[3]

Many jobs don’t pay enough to make ends meet

Many jobs in Minnesota pay less than what it takes to support a family. The Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development calculates that both adults in a typical family of three need to earn $17.80 per hour to afford their basic needs.[4] This basic needs budget only includes necessary expenses such as food, child care, housing, and health care. It does not include savings, entertainment, or vacations.

The state’s median wage was $21.45 in 2018 – comfortably above a basic needs budget for a family of three. But for workers in lower-paying jobs, it’s a different story. Twenty percent of Minnesota workers made less than $14 an hour, which isn’t enough to meet a basic needs budget for even a single worker without children.

This is in part because there are just not enough living-wage jobs. At the end of 2018, 9 of the 10 occupations with the highest number of job openings in Minnesota didn’t pay a median wage that was enough to cover the basic needs of a single worker with no children. These included jobs in food preparation and service, personal care, and administrative support.[5]

Some Minnesotans find it particularly challenging to get a living-wage job, such as workers with lower levels of formal education. In 2018, over half of Minnesota’s workers without a college degree made less than what it takes to support a family of three.

People of color more likely to face hurdles to getting ahead

People of color and indigenous people are integral parts of the state’s economy: they participate in the labor force, build businesses, and contribute to thriving Main Streets, all the while facing substantial structural barriers to economic security. While Minnesota might be a thousand miles from the Mason-Dixon Line and the history of Jim Crow, our state too has a legacy of racism and discrimination against people of color. Minnesota implemented housing policies like redlining in the mid-20th century that segregated people of color and limited their education and job opportunities.[6] Our state also has been a site of violence, theft, and oppression towards indigenous people – from colonization of their land, followed by forced removal, and subsequent violation of the treaties made with those sovereign nations. The combination of harmful policies and actions has meant that for generations and continuing to today, BIPOC Minnesotans have had less economic opportunity and barriers to building wealth and the foundations of what is called the American Dream.

Minnesota has a higher labor force participation rate than the national average, which means a greater share of our population aged 16 and older either have or are looking for a job. Many communities of color participate in the labor force in equal or higher rates than the state average. Labor force participation for white and African-American Minnesotans is 70 percent, and 72 percent for Hispanic Minnesotans. [7]

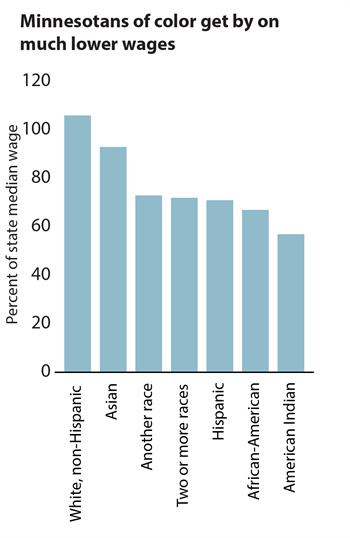

Yet people of color and indigenous people face lower earnings and higher rates of unemployment and underemployment. For example, the median earnings for African-American Minnesotans is $26,200 a year and for Hispanic Minnesotans it’s $27,900 a year. Meanwhile, indigenous people in Minnesota earn $22,500 a year.[8] Translating these earnings into hourly wages, none of these earnings are enough to meet a basic needs budget for a single worker without children.

People of color and indigenous people are also unemployed and looking for work in higher numbers. In 2018, while the state unemployment rate was a little over 3 percent, 3.8 percent of Asian, 5.7 percent of Hispanic, 7.6 percent of African-American, and 13.9 percent of indigenous people in Minnesota were unemployed. People of color are also more likely to be underemployed, defined as when a worker needs full-time employment but is only working part time, or is working in a job that doesn’t make full use of their skills. While the overall underemployment rate in 2018 was 5.4 percent, African-American Minnesotans were almost twice as likely to be underemployed.

We know that communities of color contribute to the state’s economy in many ways – including owning about 9 percent of the state’s small businesses.[9] But they also often face barriers to economic security, from the lack of public investment in schools or transportation options in their communities to discrimination in the labor market. With people of color making up an ever larger share of our workforce, it’s crucial for the state’s economic future that all Minnesotans have the opportunity to reach their fullest potential in the labor market.

Policies to boost incomes and support workers can make a difference

Policy choices play an important role in building a future where all Minnesota workers benefit from the economic growth they help create. As they act to address the health and economic impacts of COVID-19, policymakers should be informed by an understanding of which workers were already struggling before the pandemic hit and are facing the greatest hardship right now. Policymakers can ensure that Minnesotans’ hard work translates into better living standards for themselves and their families by advancing:

- Responses to the public health and economic impacts of the coronavirus that prioritize those most struggling to get by, including low-wage Minnesotans and people of color;

- Policies that improve wage and job quality standards, such as expanding access to earned safe and sick time and paid family leave;

- Tax policies that boost the wages of struggling families and narrow, rather than amplify, income inequality, such as expanding the Working Family Tax Credit to more Minnesota workers;

- Public investments that ensure Minnesotans can get the education and training they need, can afford child care, and can live near and get to good jobs; and

- Actions that explicitly address and respond to the policies, practices, and other barriers that contribute to racial inequities. This could include formalizing practices that require policymakers to disaggregate data and consider the impact of legislation on racial equity during the policymaking process.

Minnesota can only truly succeed when all workers are able to make ends meet and get ahead. Policies that dismantle barriers to economic success both in the current crisis and in the recovery to come build a stronger future for us all.

By Clark Goldenrod

[1] Except where otherwise noted, data in this report come from analysis by the Economic Policy Institute of Current Population Survey and Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Latest figures are from 2018, and all wage calculations are inflation adjusted to 2018.

[2] This analysis defines low-wage workers as workers in the 20th percentile and high-wage workers as those in the 90th percentile. Median-wage workers are defined as those who earn the median wage, the wage at which 50 percent of workers earn wages below and 50 percent earn above.

[3] Minnesota Budget Bites, Federal data affirm Minnesota’s choice to raise the minimum wage, March 2015.

[4] A typical family is defined as one adult working full-time, the other working part-time for a combined 60 work hours a week. Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, Cost of Living in Minnesota, 2018.

[5] Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, Job Vacancy Survey, 2017.

[6] Iowa Policy Project, Race in the Heartland: Equity, Opportunity, and Public Policy in the Midwest, October 2019.

[7] These statistics focus on African-American and Hispanic workers of color only because of data limitations. The data source used does not provide information about other communities of color, nor does it allow us to distinguish among subgroups within the Hispanic and African-American communities.

[8] Wage and unemployment rate data in this analysis come from the 2017 American Community Survey.

[9] U.S. Small Business Administration, 2018 Small Business Profile – Minnesota, 2018.