One of the most serious likely consequences of Minnesota adopting a constitutional supermajority amendment would be shifting the costs for providing vital public services to the local level and increasing pressure on property taxes.

The proposed amendment (House File 1598 and Senate File 1384) would require a three-fifths (60 percent) supermajority vote in both bodies of the Legislature to raise taxes. The supermajority requirement would apply to any increase in the income tax, sales tax, or a new statewide tax, as well as any increase in local governments’ authority to raise taxes. While that may sound like a check on property taxes, the outcome is likely to be the opposite.

Restricting the ability of state legislators to raise taxes will make it harder to pay for the services Minnesotans expect their government to provide. Policymakers will have to look for other ways to fund those services. Past experience in Minnesota has shown that the inability to raise taxes at the state level leads to more pressure on tuition, fees and property taxes.

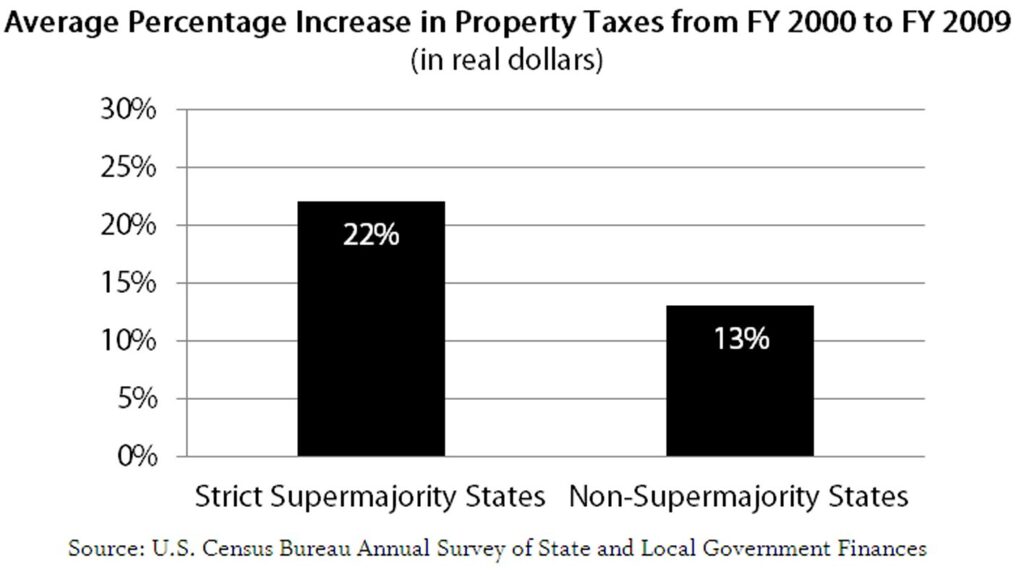

Recent U.S. Census Bureau data reveals that over the past decade, on average, states with strict supermajority requirements had increases in property taxes that were much higher than in states without such requirements.[1] Nine states already have stringent supermajority requirements, similar to the proposal being considered in Minnesota.

Between 2000 and 2009, states with strict supermajority requirements saw state and local property taxes rise an average of 22 percent, after adjusting for inflation, while property taxes in states without any supermajority requirements for tax increases rose an average of just 13 percent. California, a strict supermajority state, saw property taxes increase by 41 percent in real dollars, even though that state also has a constitutional limitation on property tax growth.

This is not the right direction for Minnesota. Creating a supermajority requirement to raise state taxes makes it more likely that policymakers will turn to other ways to balance the budget that only require a simple majority vote, such as cutting funding to cities, counties and school districts; or shifting the responsibility for funding services to the local level. In the end, Minnesota businesses and residents will likely pay more through their property taxes. We have already seen increased pressure on property taxes in recent years, as the state addressed its revenue shortfalls in part by cutting funding to cities and counties and delaying funding for schools.

The impact of this cost-shifting could further increase disparities in economic opportunities and availability of quality services across the state. Communities with fewer resources are least likely to be able to make up the difference from state budget cuts.

Supermajority requirements come with a promise of holding down taxes. But the more likely result is increased pressure to raise local property taxes. Policymakers should make tax and budget decisions directly, not through rigid formulas in the constitution that create unintended consequences.

[1] This data represents the author’s analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances. The nine strict supermajority states are Arizona, California, Delaware, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon and South Dakota. These states have adopted a constitutional supermajority requirement that applies to all major sources of revenue, similar to the proposal being considered in Minnesota. Another seven states also have some kind of supermajority requirement in place (Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri and Washington), but these states are not included in the analysis because their supermajority requirements are statutory or otherwise significantly different from what has been proposed in Minnesota. However, even if the states with weaker supermajority requirements are included in the analysis, the average increase in property taxes is still higher in supermajority states (19 percent) than in non-supermajority states (13 percent). Wisconsin, which has a statutory supermajority requirement, is included as a non-supermajority state in this analysis because its supermajority law was not passed until 2011.