Affordable, dependable child care helps children thrive, parents work or go to school, and employers fill essential job openings. But for too many Minnesota families, reliable child care is out of reach due to high costs and long waiting lists for assistance. Funding for Basic Sliding Fee Child Care Assistance has yet to recover from monumental cuts made nearly two decades ago. What’s more, the coronavirus pandemic is creating greater strain on the child care system. The strength of the state’s economy depends on greater participation of Minnesotans in the labor force. Minnesota can’t afford to leave working parents on the sidelines because they lack access to affordable child care.

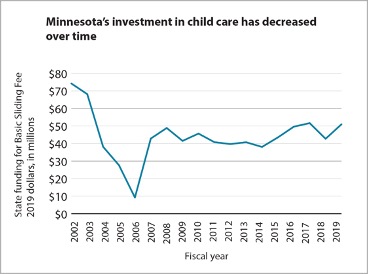

Funding for Child Care Assistance has not kept pace with what families need. The state’s funding for Basic Sliding Fee Child Care Assistance has dropped by 25 percent since FY 2003 when inflation is taken into account, and thousands fewer families are able to participate.[1]

The lack of investment in Child Care Assistance is harming child care providers, too – which limits parents’ choices. Low provider reimbursement rates mean that many providers that accept Child Care Assistance do so at a financial loss.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these long-standing challenges and the fragile child care system is now deeper in crisis. Child care providers are experiencing increasing financial difficulties and parents, including many essential workers, have enormous challenges finding care for their children while they go to work or school – either in-person or remotely.

Making sure all families can afford the child care that meets their needs is one component of ensuring a strong start for all Minnesota children. Minnesotans of color are more likely to struggle to afford child care because they face greater barriers to accessing good jobs and good schools, in part due to a history of inequitable policy choices that limited their opportunities and disinvested in their neighborhoods.

How Child Care Assistance makes child care more affordable for families across Minnesota

Minnesota’s Child Care Assistance Program is an important part of the child care and early learning landscape for families in all 87 counties (see Appendix 1 for county-specific information about the number of participating families and providers). Families can use Child Care Assistance to bring down the costs of stable, nurturing care for their children so that parents can work or further their education and training. Parents can choose the provider and location that works best for their family.

Child Care Assistance includes two components: Basic Sliding Fee and MFIP Child Care Assistance. About 15,000 families participate in Child Care Assistance, with the numbers roughly split between Basic Sliding Fee and MFIP Child Care Assistance.[2] Basic Sliding Fee is available to low- and modest-income families who meet income guidelines. The very low-income families participating in MFIP, the Minnesota Family Investment Program, are automatically eligible for MFIP Child Care Assistance.

Minnesota’s Child Care Assistance Program covers children from infancy through age 12, or age 14 if they have special needs. This distinguishes Child Care Assistance from other care options that are only available for younger children. In the families who receive Child Care Assistance, about 38 percent of children are school-aged, meaning six or older.[3]

Families can become eligible for Basic Sliding Fee if their incomes are below 47 percent of the state’s median income for their household size. Once they qualify, families remain eligible until their incomes reach 67 percent of the state median income. For example, a household of four can become eligible for Basic Sliding Fee with an income of $51,095. This household would remain eligible until they earn about $72,838 at their regularly-scheduled redetermination period. Additionally, there is some flexibility to temporarily go above this income limit so that minor changes in income, like a small raise or more work hours, doesn’t suddenly disrupt access to child care.[4]

Providers in all Minnesota counties work with families and the state to accept Child Care Assistance payments. When a child care provider accepts a family participating in Child Care Assistance, the state pays a portion of the child care costs through a reimbursement rate and the family pays a co-payment. State reimbursement rates are based on what child care providers charge in each county, but only cover a portion of the cost. The parent co-payment is calculated on a sliding scale based on family income that increases as the family’s income rises.

Child care is an expensive necessity for families

Child care can be one of the largest expenses that families with children face. The average annual cost for an infant is $8,528 at an in-home care provider and $16,172 at a child care center.[5] As a point of comparison, undergraduate tuition at the University of Minnesota is about $13,000 – making a year of college tuition cheaper than a year of infant care at a center.

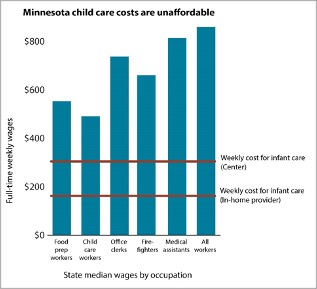

The high cost of child care is unsustainable for many Minnesota workers. As shown in the graph below, paying for an infant in a child care center would take over 55 percent of the wages for a food prep worker, nearly half the paycheck for a firefighter protecting and serving their community, and more than a third of the income for a typical worker earning the median wage in Minnesota.[6]

A survey conducted by Wilder Research found that the high costs of child care mean that many parents instead rely on a patchwork of informal care arrangements that may not reflect their family’s needs: 35 percent of low-income households in Minnesota reported that they felt they “had to take whatever arrangement they could get.”[7] Parents of color experienced this situation at a higher rate than white parents – 44 percent versus 27 percent.[8] A lack of consistent child care can make it difficult for a parent to get to class or their job, and the disruption can also have a negative impact on their children. Frequent changes in care arrangements are correlated with poor acquisition of school readiness skills, bullying behavior, and acting out.[9]

A history of policy choices that limited access to education and good jobs has contributed to shameful racial economic disparities in our state. Minnesotans of color are more likely to be earning lower wages and therefore more likely to access Child Care Assistance to bring down the cost of child care. That makes investing in affordable child care one component of providing an equitable start for all Minnesota kids.

Child care is an important building block to support children well into their futures. Research shows that access to appropriate child care settings can go a long way towards getting children from all backgrounds ready for school.[10] Research also demonstrates that children living in poverty who experience quality early childhood education programs are more prepared for school, both behaviorally and academically.” [11]

Funding for and access to Basic Sliding Fee Child Care Assistance has dropped dramatically

Massive cuts to Child Care Assistance were made in the 2000s, along with policy changes that harmed families and providers. Despite some recent improvements and reinvestment, Child Care Assistance funding has never fully recovered and is too low to serve all eligible families.

State funding for Basic Sliding Fee has dropped by 25 percent since FY 2003 when accounting for inflation – from $68 million in FY 2003 to $51 million in FY 2019.[12] That is largely the result of massive cuts to Child Care Assistance totaling $250 million that were passed in the 2003 and 2005 Legislative Sessions but have never been fully restored.[13]

Federal dollars and a small county contribution of about $3 million per year also fund Basic Sliding Fee, but total funding dropped from an inflation-adjusted $143 million in FY 2003 to $106 million in FY 2019. That is a decrease of 26 percent.

Additionally, the devastating funding cuts enacted in 2003 and 2005 were accompanied by major reductions in eligibility, shrinking the number of Minnesota families able to access Child Care Assistance. Policymakers lowered the income that families could earn and still qualify for assistance, increased family co-payments, and froze provider reimbursement rates.

This disinvestment and accompanying policy changes have had real consequences for Minnesota families. Today, 5,256 fewer families participate in Basic Sliding Fee than in FY 2003, even though the need for affordable child care is as strong as ever. Nearly 2,000 families are on waiting lists for Basic Sliding Fee, and other families are eligible but not on waiting lists.[14]

Higher provider reimbursement rates would support parental choice and supply of providers

Deterioration in the state’s payments to providers through Child Care Assistance limits families’ child care options. While recent state actions have increased provider rates, the reimbursements are still quite low at only 25 percent of the typical market rate for child care. That is a significant financial hardship for many providers. And, the rates are based on 2018 data – meaning they are already out of step with the current market rates for child care.

If the combined parent co-payment and state contribution do not fully cover the rates charged by a provider, one of three things can happen: parents can be asked to pay more to cover the difference, the provider needs to fill in the gap with other resources, or the provider will take a financial loss.

Many child care providers are small businesses that eke by on razor-thin profit margins, and therefore they may choose not to accept families participating in Child Care Assistance. Asking providers to accept families at a financial loss serves no one well; neither does asking parents to come up with additional funds in their already stretched budgets.

Parents are now choosing from a significantly smaller pool of providers

From 2015 to 2019, the number of providers registered to participate in Child Care Assistance dropped by about a third.[15] This is happening at a time in which the overall number of child care providers is not keeping up with the need. Minnesota is only gradually adding child care centers and the number of family child care locations are shrinking.[16] The loss of family child care providers is of particular concern in Greater Minnesota, where they make up two-thirds of child care capacity; a much larger share than in the Twin Cities metro area.[17]

The challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic are also creating shocks to the system that will have repercussions on the availability of child care spots for years to come. Providers have faced significant challenges during the pandemic: some have seen their numbers decrease as parents are more likely care for children at home due to unemployment or remote work; cleaning supplies and processes have introduced significant additional costs; and requirements about quarantines for staff and families following COVID-19 exposures have created uncertainty around staffing and attendance.

Today’s child care investments are building tomorrow’s Minnesota

Affordable child care is a crucial building block of family economic security and our future economic success as a state. Minnesota should provide budget-strapped families with vital access to affordable child care by boosting funding for Child Care Assistance, increasing reimbursement rates to providers, and making other needed policy changes to make the system work better for families. This investment would echo into the next generation as children benefit from having safe, consistent, and nurturing environments to grow and thrive. Employers would have an easier time filling crucial positions with workers who would not need to worry about reliable care for their kids. In other words, a strong investment in Child Care Assistance will help all boats rise now and in the future.

By Betsy Hammer

Appendix One: Monthly Average Number of Children Served and Minnesota Providers Participating in Child Care Assistance, State Fiscal Year 2020[18]

County | Monthly average number of children served by | Total number of providers participating in |

Aitkin | 32 | 12 |

Anoka | 1,737 | 152 |

Becker | 112 | 50 |

|

Beltrami |

206 |

80 |

|

Benton |

218 |

47 |

|

Big Stone | 25 |

9 |

|

Blue Earth |

336 |

73 |

|

Brown |

118 |

45 |

|

Carlton |

93 |

29 |

|

Carver |

212 |

44 |

|

Cass |

67 |

29 |

|

Chippewa |

32 |

11 |

|

Chisago |

98 |

28 |

|

Clay |

191 |

53 |

|

Clearwater |

29 |

14 |

|

Cook |

<10 |

3 |

|

Cottonwood |

25 |

14 |

|

Crow Wing |

362 |

74 |

|

Dakota |

2,051 |

190 |

|

Dodge |

126 |

36 |

|

Douglas |

100 |

36 |

|

Faribault |

27 |

17 |

|

Fillmore |

68 |

19 |

|

Freeborn |

115 |

29 |

|

Goodhue |

149 |

32 |

|

Grant |

35 |

10 |

|

Hennepin |

10,325 |

586 |

|

Houston |

55 |

22 |

|

Hubbard |

88 |

37 |

|

Isanti |

153 |

25 |

|

Itasca |

91 |

40 |

|

Jackson |

18 |

10 |

|

Kanabec |

36 |

17 |

|

Kandiyohi |

127 |

49 |

|

Kittson |

<10 |

7 |

|

Koochiching |

46 |

13 |

|

Lac Qui Parle |

<10 |

4 |

|

Lake |

20 |

6 |

|

Lake of the Woods |

<10 |

4 |

|

Le Sueur |

63 |

25 |

|

Lincoln |

15 |

6 |

|

Lyon |

128 |

40 |

|

Mahnomen |

19 |

11 |

|

Marshall |

13 |

5 |

|

Martin |

105 |

37 |

|

McLeod |

92 |

31 |

|

Meeker |

51 |

9 |

|

Mille Lacs |

134 |

22 |

|

Morrison |

67 |

32 |

|

Mower |

151 |

46 |

|

Murray |

11 |

8 |

|

Nicollet |

146 |

39 |

|

Nobles |

50 |

12 |

|

Norman |

15 |

8 |

|

Olmsted |

1,164 |

145 |

|

Otter Tail |

105 |

55 |

|

Pennington |

19 |

16 |

|

Pine |

83 |

27 |

|

Pipestone |

35 |

19 |

|

Polk |

71 |

31 |

|

Pope |

32 |

11 |

|

Ramsey |

4,545 |

277 |

|

Red Lake |

10 |

7 |

|

Redwood |

28 |

13 |

|

Renville |

39 |

15 |

|

Rice |

188 |

60 |

|

Rock |

32 |

11 |

|

Roseau |

24 |

14 |

|

Scott |

621 |

62 |

|

Sherburne |

255 |

59 |

|

Sibley |

38 |

24 |

|

St. Louis |

654 |

151 |

|

Stearns |

732 |

114 |

|

Steele |

220 |

41 |

|

Stevens |

17 |

10 |

|

Swift |

35 |

10 |

|

Todd |

46 |

19 |

|

Traverse |

<10 |

2 |

|

Wabasha |

46 |

21 |

|

Wadena |

45 |

19 |

|

Waseca |

94 |

20 |

|

Washington |

774 |

99 |

|

Watonwan |

36 |

14 |

|

Wilkin |

28 |

7 |

|

Winona |

162 |

53 |

|

Wright |

224 |

34 |

|

Yellow Medicine |

15 |

6 |

|

TOTAL |

29,027 |

3,753 |

By Betsy Hammer

[1] Minnesota Budget Project analysis of Minnesota Department of Human Services, data on Basic Sliding Fee enrollment by county and Background Data Tables for May 2020 Interim Budget Forecast. This analysis takes inflation into account.

Minnesota Department of Human Services, Child Care Assistance Program: Number of Families on the Basic Sliding Fee Waiting List, November 2020.

[2] Minnesota House Research, Child Care Assistance: An Overview, November 2020.

[3] Minnesota Department of Human Services, Minnesota Child Care Assistance Program: State Fiscal Year 2018 Family Profile, January 2019.

[4] Minnesota Department of Human Services, Minnesota Child Care Assistance Program Copayment Schedules, Effective October 2016.

[5] Child Care Aware of America and Child Care Aware of Minnesota, Cost of Care Comparisons, April 2020.

[6] Minnesota Budget Project analysis of Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development Occupational Employment Statistics data tool.

[7] Wilder Research, Child Care Use In Minnesota, 2010.

[8] Wilder Research.

[9] Urban Institute, The Negative Effects of Instability on Child Development: A Research Synthesis, September 2013.

[10] Minnesota Department of Human Services, School Readiness in Child Care Settings: A Developmental Assessment of Children in 22 Accredited Child Care Centers, 2005.

[11] First Five Years Fund, New Research Demonstrates the Importance of Early Learning — and What Comes After, November 2019.

[12] Minnesota Budget Project analysis of Minnesota Department of Human Services, Background Data Tables for May 2020 Interim Budget Projection. This analysis takes inflation into account.

[13] Minnesota Budget Project analysis of Minnesota Department of Human Services, Background Data Tables for May 2020 Interim Budget Projection. This analysis takes inflation into account.

[14] Minnesota Management and Budget, Consolidated Fiscal Note for SF 695-1A, April 2015.

[15] Minnesota Budget Project analysis of Minnesota Department of Human Services data. See Minnesota Child Care Assistance Program: State Fiscal Year 2019 Provider Profile.

[16] Minnesota Department of Human Services, Legislative Report: Status of Child Care in Minnesota, 2018, February 2019.

[17] Center for Rural Policy and Development, CRPD Hears From Child Care Providers, April 2019.

[18] Minnesota Budget Project analysis of Minnesota Department of Human Services data, January 2020.