The federal Reconciliation Bill (H.R. 1) that was passed into law in July will make life harder for everyday folks across our country. This law’s tax provisions favor the rich while doing little to help average Americans. The bill extends many parts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 that otherwise would have expired – and repeats the TCJA’s pattern of providing the largest tax cuts to higher-income people. It creates a few new tax provisions that proponents claim benefit working folks, but in reality, these reach few Americans and are temporary.

The skewed tax provisions are part of a sweeping package that harms the working class by taking away health care coverage and food support, targeting immigrants and their families, and raising costs for health care and other basic needs.

The bulk of tax benefits go to the rich, while working-class Americans get very little

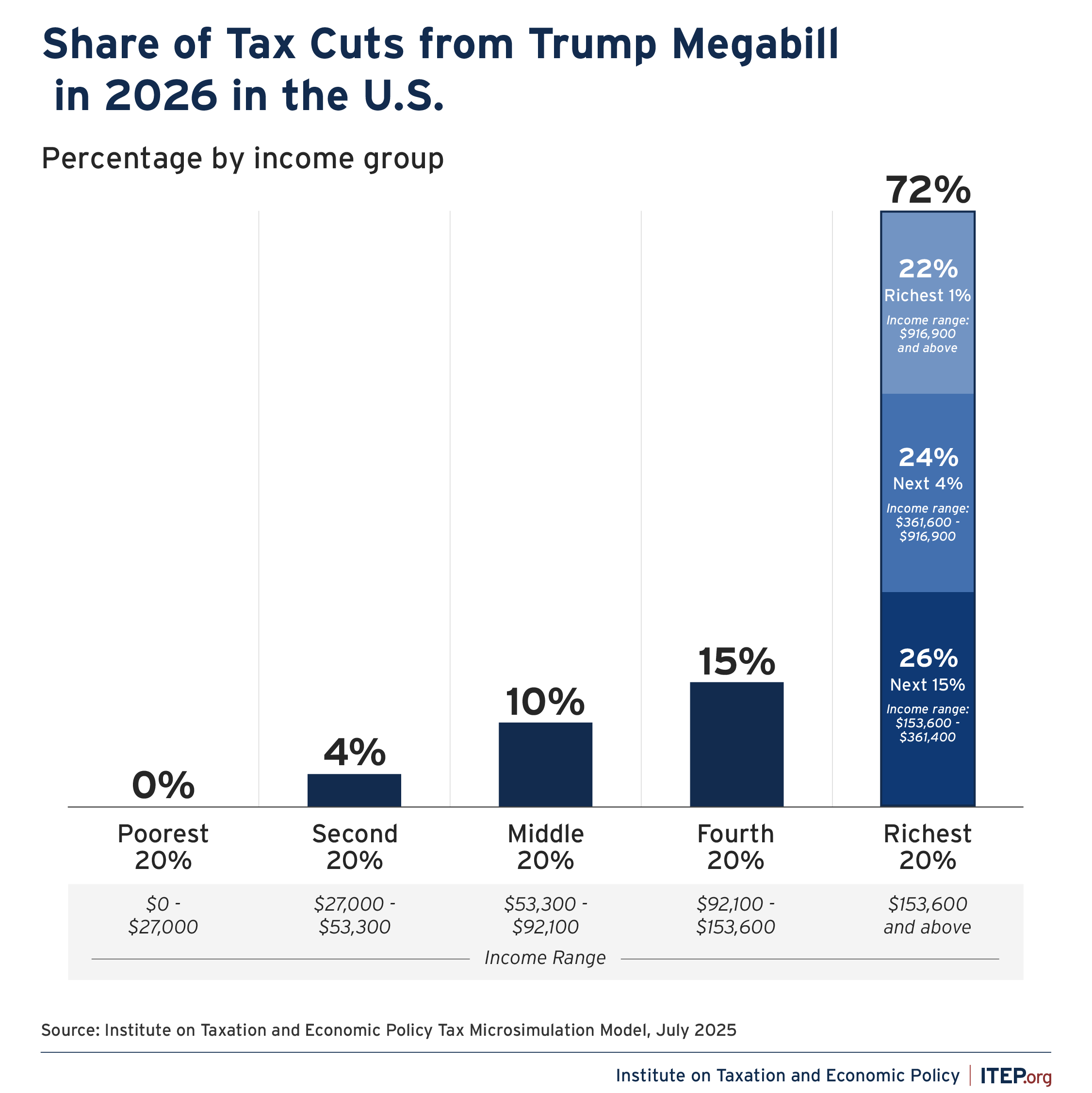

The American people generally will not see the “Economic Lifeline” that the Trump Administration promised from H.R. 1 (also called the One Big Beautiful Bill or Megabill). The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy dug into the details, and their analysis demonstrates how this bill primarily benefits the wealthy. The analysis shows that households making less than $92,000, which make up 60 percent of the population, will only see 14 percent of the total net tax cuts coming out of the Reconciliation Bill in 2026. Meanwhile, the 20 percent of households making nearly $154,000 or more per year will be getting 72 percent of the total tax benefits, with a remarkable 22 percent of the tax cuts going to the top 1 percent.

The richest 1 percent of Americans will collectively get $117 billion in tax cuts in 2026, which is more than the total tax cuts going to the 60 percent of households making $92,100 or less. Instead of using this huge sum of money to make transformational positive change, the federal Reconciliation Bill gives it away to the most well-off. That $117 billion could pay for tuition and room and board for every college senior in the country for a year or nearly cover the remaining cost to house every unhoused person in the U.S. for 6 years.

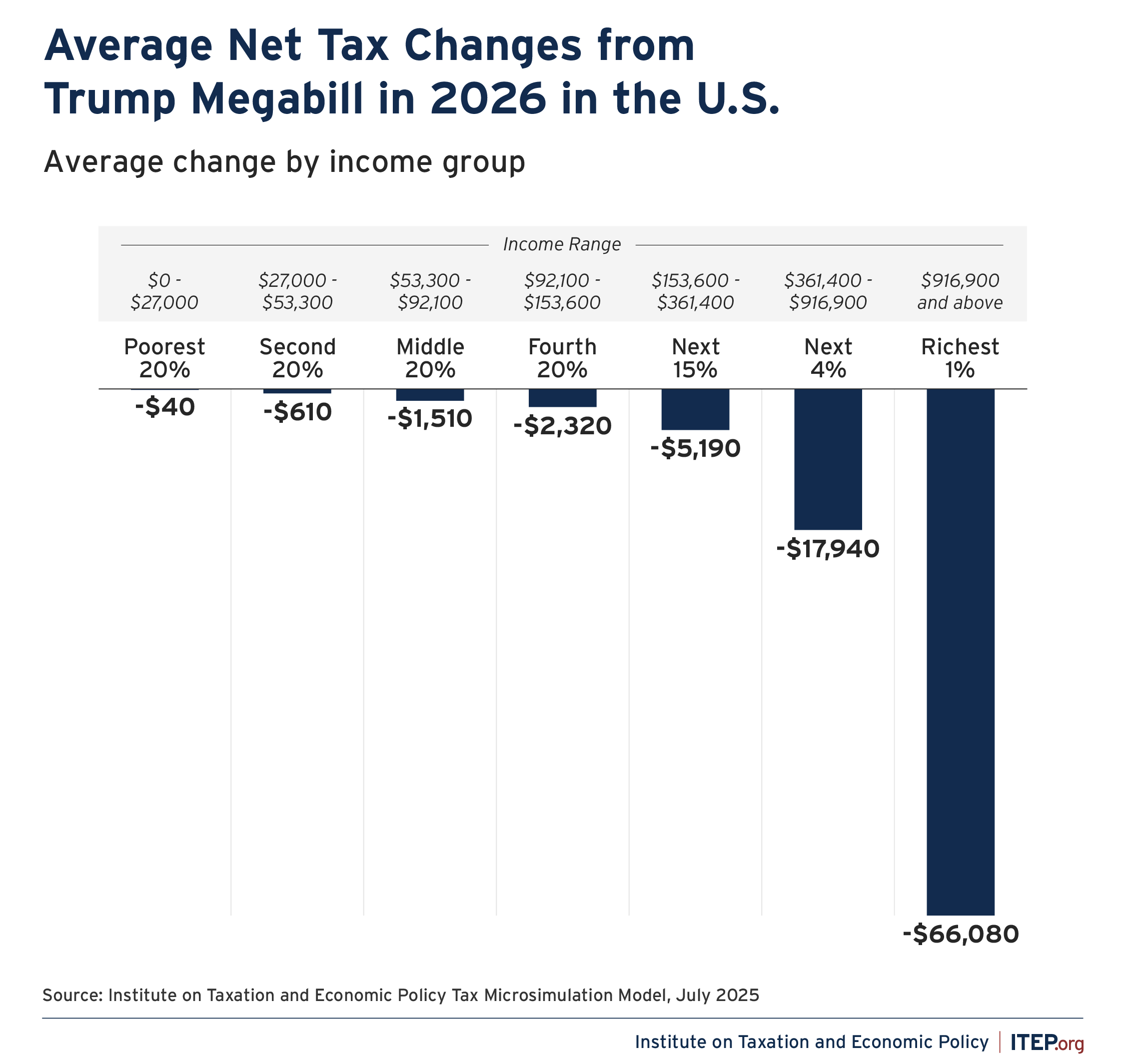

When looking at average tax cuts, it’s clear that the big tax cuts are for the wealthy, and the much smaller ones are for everyone else. For the 2026 tax year, middle-income Americans making between $53,300 and $92,100 will see an average tax cut of $1,510, and lower-income Americans, making less than $27,000, will get an average tax cut of just $40. Conversely, the top 1 percent of households making over $916,900 will get an average tax cut of $66,080.

This means that next year, low-income Americans could get about two weeks’ worth of diapers with their average tax cut, while the top 1 percent could buy a brand-new luxury vehicle with their average tax cut.

It is important to note that much of the tax changes illustrated above are not new. In H.R. 1, policymakers have acted to maintain TCJA tax provisions that are already in place but were scheduled to expire at the end of this year. However, when compared to people’s tax situation now, the bill on average raises taxes on folks making less than $27,000 by $100 in 2026 and the middle-class tax cuts become much smaller. That’s because H.R.1 largely extends the TCJA, but it does not similarly extend enhanced premium tax credits that help bring down the cost of health insurance, which are scheduled to expire at the end of 2025.

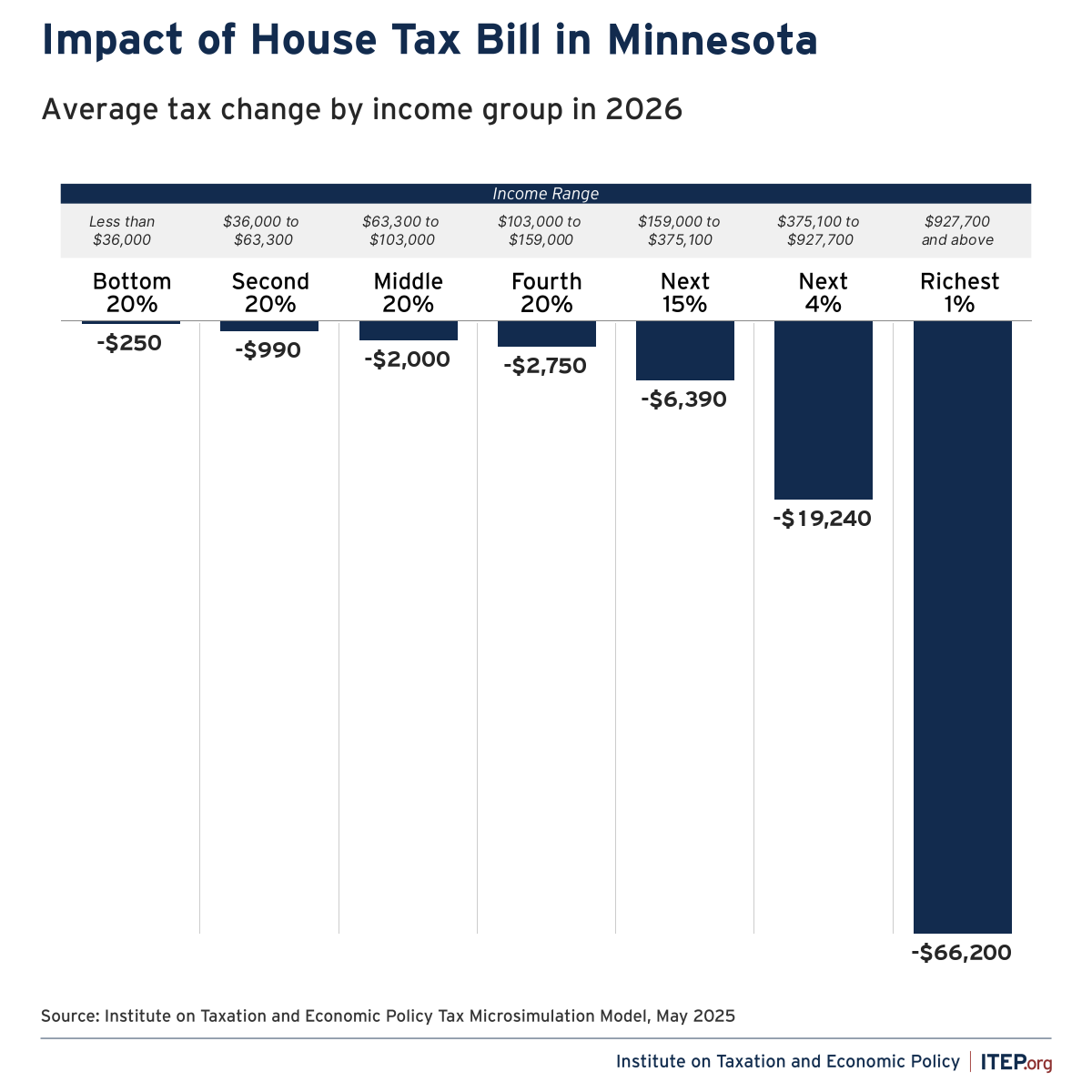

High-income Minnesotans benefit most from H.R. 1

The pattern of larger tax cuts for higher-income people also appears when looking specifically at how Minnesotans are impacted by H.R. 1’s tax provisions. The 20 percent of Minnesotans making less than $36,000 will get an average federal tax cut of $240 in 2026. In contrast, the richest 1 percent, making more than $927,700, will get an average tax cut of $52,370 – more than 200 times bigger. Minnesota’s top 1 percent of households will collectively get $1.6 billion in tax cuts in 2026.

Tax provisions for the rich are costly while provisions supposedly for everyday people fall short

H.R. 1’s massive tax cuts come primarily through extension and modification of TCJA provisions that were scheduled to expire, as well as additional business tax breaks. Taken together, the TCJA and business tax provisions of the law provide the largest tax cuts to high-income households, and combined have a net cost of $567 billion in 2026 alone.

Nearly all of the largest tax-cutting provisions in the federal Reconciliation bill provide larger tax cuts for the rich. Some examples include:

- TCJA-related changes to income tax rates and brackets, which will cost $204 billion in 2026.

- Extension of the TCJA’s pass-through deduction, which is a tax benefit for households with certain kinds of business income, at a cost of $79 billion in 2026.

- Reductions in the Alternative Minimum Tax, which weaken its purpose of limiting how much higher-income people can use tax breaks to reduce their taxable income, at a cost of $142 billion in 2026.

In addition, the bill includes other tax cuts for businesses that will cost $165 billion in 2026.

Meanwhile, the new tax provisions purported to be for average Americans are smaller, poorly designed, and expire in a few years. These include things like a limited tax exemption for some workers who earn tips, a tax deduction for some overtime pay, a new tax deduction for some seniors, and a limited ability to take a tax deduction for loan interest for certain car loans. All of these so-called “middle-class tax cuts” combined total just $58 billion in 2026, a tenth of what will go toward TCJA extension and business tax cuts.

These policies are not effective at lifting up low- and middle-income people. They are structured in ways that do little to nothing for the lowest-income folks, and they prioritize certain groups of people, such as seniors and people who work jobs that get tips or overtime, instead of pursuing other policies that would address the economic challenges facing working-class Americans regardless of their age or line of work. All of these tax cuts combined would only benefit about 30 percent of households, with the tax deductions for tips and overtime going to only 3 percent and 9 percent of U.S. households, respectively. Though these tax cuts were advertised to help average Americans to better make ends meet, ITEP finds they won’t do much for the 60 percent of taxpayers making less than $92,100, who can expect to see $380 or less in tax cuts from these provisions in 2026. Moreover, all of these provisions expire at the end of 2028.

Furthermore, H.R.1 also falls short for struggling families because it continues to leave behind low-income families who need the Child Tax Credit the most to get by. The federal Child Tax Credit provides families with more resources to afford the costs of raising thriving children. The reconciliation bill makes the expansions to the CTC temporarily enacted under the TCJA permanent, rather than expiring at the end of 2025. The new law also increases the maximum amount of the credit that families may qualify for but still fails to fix a flaw in the current CTC that results in 17 million children getting smaller credits or none at all because their families’ incomes are too low. The Child Tax Credit will also be taken away from about 2 million children because of new citizenship restrictions added by the law.

Small tax cuts are outweighed by the harm from other federal policies

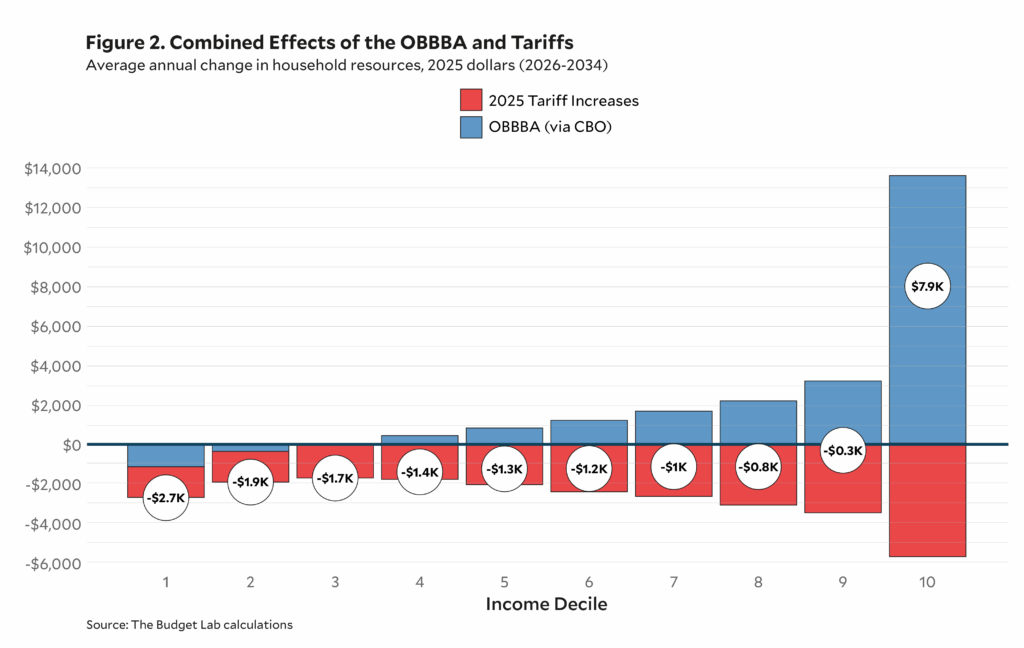

For most everyday people and their families, the relatively small amount of benefit they would get from the federal Reconciliation Bill tax provisions will not make much difference when the entirety of the harmful impacts of H.R. 1 and other federal policies are taken into account. The Reconciliation Bill partially pays for the tax cuts by making the largest funding cuts in American history to health care through Medicaid and food assistance through SNAP. As the graphic from the Budget Lab at Yale below shows, H.R. 1’s tax provisions, the cuts in basic needs services, and the ways that the Trump administration’s tariff policies will increase costs for consumers combined will result in every income group with household incomes below $218,026 suffering a reduction in their average household resources over a 10-year period.

A better tax bill would prioritize everyday people instead of making the rich richer

Instead of more giveaways to the wealthy, policymakers should have focused on making it easier for more people to afford their lives and build stronger futures. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has outlined what a better tax bill could have looked like. A better bill would not have paid for high-income tax cuts by slashing funding for health care and food assistance for millions of people. A better bill would lift up struggling families, regardless of income or immigration status, through extensions and expansions of income-boosting tax credits like the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit and would bring down the cost of health insurance through the Premium Tax Credit. And a better tax bill would have raised revenues by making sure the wealthy and most profitable corporations do more to fund essential public services so that more people have what they need to survive and thrive.