As the United States enjoyed a lengthy period of economic growth following the Great Recession, the benefits did not reach all people equally: many folks were left behind. While some saw the value of their stocks hit record highs, many workers saw their wages stagnate. Household basics, like food, rent, and medicine, grew less and less affordable. And the hardships fell disproportionately on people of color, Indigenous people, and immigrants. Even in the good times, the gap in economic well-being between white Americans and people of color grew wider.[1]

Now, new data from the Census Bureau illustrates the staggering increase in hardship as a result of the coronavirus pandemic and burgeoning economic recession.[2] And the burden falls particularly on people of color, who benefitted the least from the economic boom times and today can least absorb the blow.

These data demonstrate the need for bold policy responses, at multiple levels of government, to meet the public health and economic security needs of everyday Americans, targeted to those who need it most. These include policy measures to ensure people have enough to eat, a secure place to call home, and financial resources to make up for lost wages. These actions would lessen the suffering the pandemic and recession has brought to so many, and it would put the country on a stronger path to economic recovery.

Hunger is increasing

Access to food is vital to staying alive, as well as for having the energy to go to work or succeed in schoolwork. But not all Minnesotans are able to consistently access the food they need – and there has been a dramatic increase in hunger since the coronavirus pandemic hit. As of the first week of July, 326,000 Minnesota adults live in households that sometimes or often don’t get enough to eat.

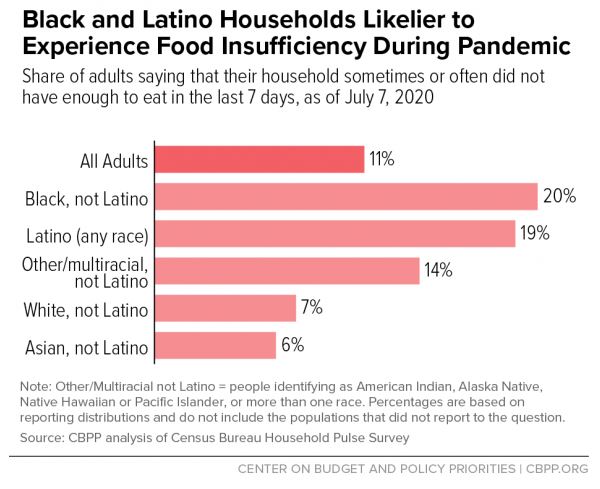

Across the United States, about one in five Black and Latino people across the United States are experiencing food insecurity. Since the pandemic hit, there has been a 14 percent increase in the number of Minnesotans turning to food assistance through SNAP to put food on the table.

Families struggle to get enough healthy food to eat with the amount of help they get from SNAP, even at the best of times. A further boost in SNAP is needed to respond to the rising cost of groceries. A 15 percent boost in SNAP, for example, would mean an extra $25 per person per month – a modest but important increase. Additional food support is crucial to better ensuring families and kids have the food they need to thrive, and would also stimulate our economy as families purchase groceries at local stores.[3]

An eviction crisis looms

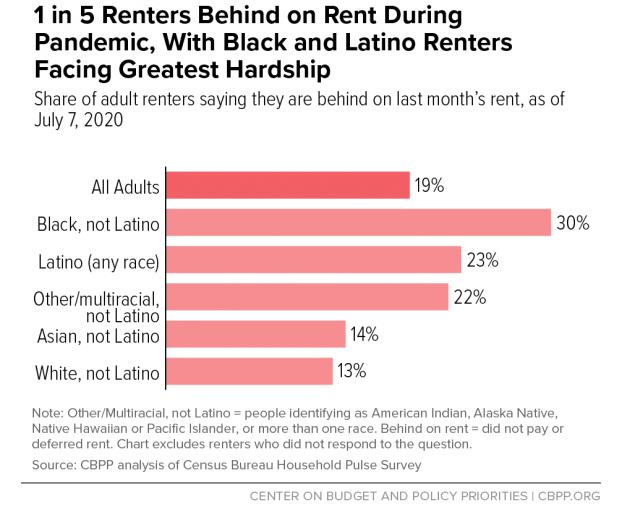

Housing is also a necessity, and we are at a critical juncture: as of the first week of July, one in five adult renters in the U.S. – over 13 million people – are behind on rent. In Minnesota, our numbers are only marginally better, with 16 percent of households falling behind. And the trend is going in the wrong direction, with the percentage of Americans behind on rent increasing over time.

Those numbers are a staggering overview, but a deeper dive presents an even more dire picture for people of color: about one in three Black adults in the U.S. and one in four Latino adults are behind on rent.[4] Many children are affected, too: one in four households with kids are behind on rent. That works out to be about seven million kids in the U.S.

This housing crisis is not uniquely created by the pandemic; the number of households struggling to afford rent has been increasing for decades. When accounting for inflation, rents increased over 13 percent from 2001 to 2018 while renters’ wages stayed flat. And rent takes up a huge amount of household income for many folks: 10.7 million households – or 23 million Americans – spent over half of their incomes on rent in 2018.

Now, with the pandemic and recession raging, policies that pause evictions may protect some households temporarily, but there is an urgent need for additional housing assistance, continuing the eviction moratorium, and other steps to prevent an unprecedented wave of homelessness across the country.

More people are out of work than since the Great Depression

Unemployment is yet another realm where the burden is falling hardest on those with the least financial cushion to get through. The United States’ unemployment rate quadrupled between February and April, and has reached levels not seen for nearly a century. Some 20 million jobs were lost in April 2020 – which is 10 times greater than any monthly job loss number since recordkeeping began in the late 1930s.

More recent numbers from June show a slight improvement as a result of economic re-openings in some parts of the country, but the national 11.1 percent unemployment rate and Minnesota’s 9.1 percent unemployment rate are both higher than at any time during the Great Recession a decade ago. These improvements are likely to be short-lived as the virus takes wider hold.

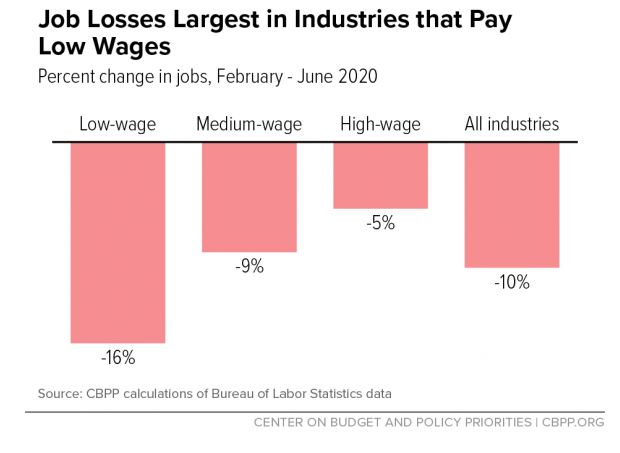

These unemployment numbers are grim. And here again, those who struggle most to get by are more likely to find themselves out of work. Though low-wage jobs make up about 30 percent of all U.S. jobs, they represent 52 percent of all jobs lost from February to June. Low-wage jobs disappeared at three times the rate of high-wage jobs during that time period.

Due to a legacy of structural racism and unequal educational opportunities, workers of color are more likely than white workers to hold low-wage jobs. The national unemployment rates by race reflect that: Black and Latino workers are much more likely to be out of work than white workers.[5]

In June, the unemployment rate was15.4 percent for Black workers, 14.5 percent for Latino workers, and just above 10 percent for white workers. Gains in employment from April to June 2020 were also disproportionate: white workers saw a decrease in unemployment of 4.1 percent, while Black workers only experienced a 1.3 percent change.

Workers won’t be able to fully get back to work until the coronavirus is contained. In the meantime, ongoing policy measures are needed to replace those lost wages – maintaining Unemployment Insurance expansions including the $600 additional weekly payment and the ability for self-employed and other usually excluded workers to qualify, as well as the food and housing assistance described above.

For workers still on the job but struggling to make ends meet because of low wages or reduced hours, expanding tax credits for working families – like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit – are an additional way to boost incomes and reduce poverty.

Unprecedented hardships need a strong policy response

Policymakers at multiple levels of government took important steps in the early stages of the pandemic so that Minnesotans could stay healthy and pay the bills. But it hasn’t been enough to stave off an increase in hunger, housing insecurity, and job loss. It’s clear that both the health and economic effects will be with us for months to come, and more action is needed. The danger at this point is not that policymakers will take too much action, but rather that they will do too little. The result would be deepening racial inequality, painful hardships, and a deeper and longer-lasting recession.

By Betsy Hammer

[1] See Minnesota Budget Project, Recession policy responses that do not center Minnesotans of color likely to widen racial disparities, August 2020.

[2] Except where otherwise noted, all data in this issue brief are from Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, More Relief Needed to Alleviate Hardship: Households Struggle to Afford Food, Pay Rent, Emerging Data Show, July 2020.

[3] This represents the increase in SNAP enrollment from February to May 2020.

[4] These figures are the share of adults in rental housing that are behind in their rent.