In an era of income inequality and growing concentration of wealth, a new 50-state study analyzes whether state tax systems make income inequality better or worse. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) finds that Minnesota’s tax system reduces income inequality in our state. Minnesota ranks 50th on ITEP’s Tax Inequality Index, with only the District of Columbia having a stronger impact on reducing inequality.[1]

Policy choices matter. In their Who Pays? report, ITEP highlights a number of things that Minnesota does right to build a fairer tax system. These include:

- A graduated personal income tax that also limits itemized deductions for upper-income taxpayers and includes a tax on high-earner investment income;

- Income-targeted tax credits including the new Child Tax Credit, the Working Family Credit, property tax refunds for homeowners and renters, and the Child and Dependent Care Credit;

- An estate tax;

- Higher property tax rates on higher-value properties;

- Requiring combined reporting for the corporate income tax; and

- Excluding groceries from the sales tax.

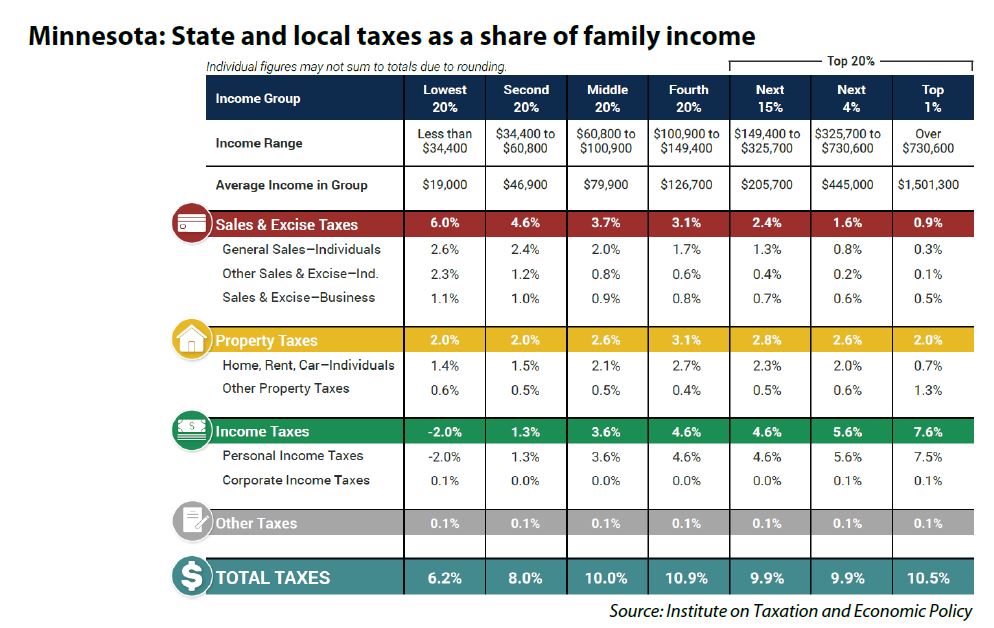

For each state, ITEP’s study measures what share of their incomes households of different income levels pay in taxes. They find that Minnesota and the other states with more equitable tax systems follow a similar recipe: a highly progressive income tax with relatively few exemptions that benefit the wealthy, plus income-targeted tax credits, which offset the regressive impacts of property and sales taxes.

As the results from Minnesota illustrate, income taxes are usually progressive, meaning that high-income households pay a larger share of their incomes in that tax than those with low- or middle-incomes. In contrast, sales and property taxes are regressive — lower-income people pay a higher share of their incomes in those taxes than high-income people.

Unfortunately, most other states have taken a different approach. Nearly every state has an “upside-down” tax system in which low- and middle-income families pay a much higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes than the wealthy. These regressive tax systems make the income gaps between everyday folks and the most affluent grow wider.

In the 10 states with the most regressive tax systems, which includes Florida, South Dakota, Texas, and Washington, the 20 percent of residents with the lowest incomes pay three times more of their income in state and local taxes than the wealthiest 1 percent. Their tax policy tends to be characterized by not having a broad-based income tax, but instead relying heavily on sales and excise taxes. While these states are often described as being “low tax”, they are often actually high tax states for lower-income families.

While Minnesota continues to take steps forward, some states like Kentucky are moving backwards. In the last five years, Kentucky has made a number of policy changes that raised taxes on the lowest-income residents while cutting taxes for those with higher incomes. Kentucky policymakers chose to move to a flat income tax, lowered corporate taxes, and increased the sales tax on a number of everyday goods and services. Meanwhile, Minnesota put its tax code to work in reducing income inequality by boosting the incomes of low-income households through tax credits like the new Child Tax Credit, while raising taxes on corporate profits and large amounts of investment income. In effect, these tax changes result in Minnesota’s low-income and moderate-income households paying lower shares of their incomes to fund state and local public services than their counterparts in Kentucky. The 60 percent of Minnesotans with low- to middle-incomes pay between 6.2 and 10.0 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes, while the same groups in Kentucky pays between 10.9 and 12.4 percent of their income.

ITEP also highlights how state tax policy can either reduce or exacerbate racial disparities.[2] Choices made by policymakers and across our society have created unequal opportunities between white folks and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) people in access to education, housing, and jobs, and create deep disparities in income and wealth. Inequities in many state tax systems advantage white households, who have higher rates of homeownership and investment income and thereby see the greatest benefit from tax provisions like the mortgage interest deduction or special treatment of capital gains. Minnesota has among the worst pre-tax racial income inequalities in the nation. Minnesota’s progressive income tax system narrows this gap somewhat, but we should do more to unleash the power of the tax code to advance racial equity.

In addition to exacerbating income inequality and racial disparities, unfair tax systems fail at the key function of a tax code: raising the revenues needed to fund public services so that opportunity and economic stability are available to all. When so much of this nation’s income growth goes to high-income households, state tax systems that rely more heavily on taxing low- and middle-income residents struggle to raise enough revenue to fund their children’s education, parks and public spaces, infrastructure, and other basic services.

Minnesota has taken an approach to tax policy that has paid off for the residents of our state, and there is still work to do to create a more equitable tax system that sustainably funds the public services Minnesotans want and count on. As ITEP concludes in their report, “The wide variety of results seen across states…proves that regressive state and local taxation is not inevitable. It is a policy choice.”

By Nan Madden and Haleigh Sinclair

[1] Except where otherwise noted, the data in this issue brief comes from Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, January 2024.[2] See also Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Taxes and Racial Equity: An Overview of State and Local Policy Impacts, March 2021.