The U.S. is still on the road to recovery from the Great Recession, a period of historic economic turmoil. In December 2007, the country entered a prolonged recession during which housing prices plummeted and unemployment skyrocketed. Although the recession officially ended in June 2009, the economic recovery has been slow and unsteady, leaving many families struggling to get back on their feet.

Minnesota weathered the Great Recession better than most states. As of March 2013, the state’s unemployment rate was 5.4 percent, well below the national level. However, that figure translates into more than 160,000 Minnesotans still struggling to find jobs to support themselves and their families.[1] Extended periods of unemployment can force families to tap savings meant for education or retirement and cut back on essentials, like health care or food. Instead of taking strides forward during the recovery, unemployed Minnesotans find themselves falling further behind. That has consequences for the state as a whole since continued economic growth depends on opportunities for all.[2]

A closer look at of Minnesota’s unemployment figures highlights disturbing disparities in our state. While overall unemployment is now close to the rate at the start of the recession, some Minnesotans were hit especially hard during the recession and are having a difficult time recovering lost ground, including the less educated, the young, single families and people of color.

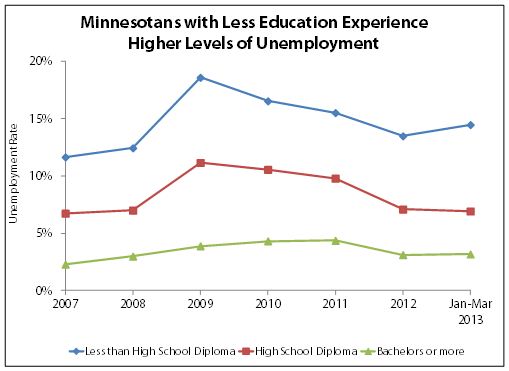

Minnesotans with Less Education Struggle in the Job Market

Minnesotans with higher levels of education had more success getting through the recession than those with a high school diploma or less. Even during the economic recovery, Minnesotans with lower levels of education are finding it far more difficult to find jobs.

- Minnesotans without a high school diploma experience much higher rates of unemployment than those with a high school diploma. As of the first quarter of 2013, almost 15 percent of Minnesotans without a high school education were unemployed. This is an improvement from 2009, when almost one in five Minnesotans without a high school diploma was unemployed. These Minnesotans still have the highest unemployment rate among all education levels in the wake of the recession.

- For those with a high school diploma, unemployment dropped to 6.9 percent by early 2013. While still higher than the state average, this was a marked improvement from the recession high of 11.2 percent.

It took longer for Minnesotans with a college degree to feel the effects of the recession, and they maintained a relatively low unemployment rate throughout that period. By early 2013, the unemployment rate for college graduates was just 3.2 percent.

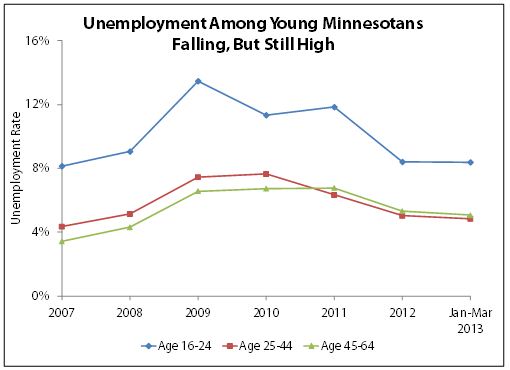

Younger Minnesotans Experience High Unemployment

Young Minnesotans looking to enter the workforce during the recession got a late start in the job market, a significant setback at a critical time in their working careers that may harm their future earnings. Unemployment has declined substantially among young adults since the recession ended, but they are still struggling in the job market.

- Young Minnesotans experienced very high rates of unemployment during the recession: in 2009, unemployment for 16- to 24-year-olds reached 13.5 percent. This figure has decreased considerably, falling to 8.4 percent as of the first quarter of 2013. However, young Minnesotans’ unemployment rate was still substantially higher than for other age groups.

- Older Minnesotans saw a more stable level of employment through the recession and recovery. For 25- to 44-year-olds, the unemployment rate was 4.9 percent in early 2013; and for 45- to 64-year-olds the rate was 5.1 percent. Both age groups saw an increase in unemployment during the recession, but have seen a fairly consistent decline in unemployment since then.

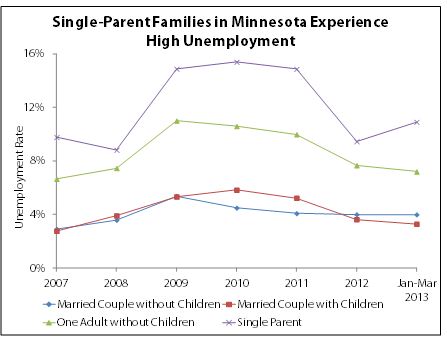

Single-Parent Families Are Struggling Through Minnesota’s Economic Recovery

Households headed by a single adult experienced much more difficulty in the job market during the economic downturn than married couples. The unemployment rate has improved for single-parent households since the recession ended, but it is still higher than for married-couple households.

A single-adult household is particularly vulnerable during an economic downturn, since there isn’t a second income-earner to help weather a stretch of unemployment.

Prolonged unemployment can also be harmful to children. The loss of wages makes it difficult to provide nutritious meals and a safe environment, and parental stress causes greater tension in the home.[3]

- Single parents experienced very high unemployment rates during the Great Recession, and as of the first quarter of 2013, 11.2 percent were still looking for work. This group consistently experiences the highest unemployment rate by household type.

- Single adults without children are also living with high levels of unemployment. Over 7 percent of single adults were looking for work in the first quarter of 2013. While unemployment among this group has improved since the recession ended, the percentage seeking employment still exceeds the statewide average.

- Married couples – with and without children – have seen fairly low levels of unemployment for the past few years, never reaching above 6 percent since the recession began. As of the first quarter of 2013, unemployment among married couples without children was 4 percent and among couples with children the rate was 3.3 percent. For this analysis, a married couple is considered unemployed if at least one adult is looking for work.

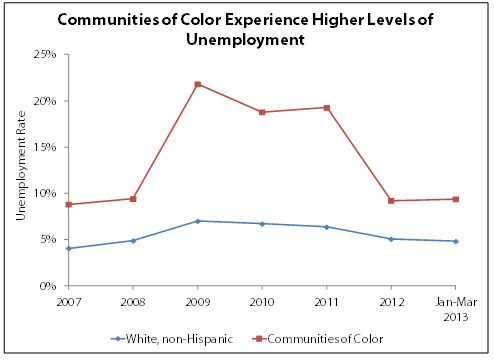

Minnesota’s Communities of Color Experience High Unemployment

Unemployment among people of color in Minnesota skyrocketed to above 20 percent during the Great Recession. As the economy improved, these communities have once again found opportunities in the workforce.

However, unemployment continues to be higher in communities of color. This in part reflects historic and structural factors that limit access to opportunities in communities of color, as well as discrimination in the labor market.[4]

- While the unemployment rate for white Minnesotans has been consistently lower, the rate for people of color jumped to more than three times the rate for white Minnesotans in 2009.

- Unemployment for all racial groups has fallen to pre-recession levels, but the unemployment rate for people of color is still 4.6 percentage points higher than for white Minnesotans.

- Many communities of color continue to experience much higher rates of unemployment. Other data sources show that the 2011 unemployment rate was 17.8 percent for Native Americans in Minnesota and 19.9 percent for African Americans in the state.[5]

Persistent Employment Disparities Should be Addressed

Many Minnesotans continue to struggle with a lack of economic opportunity four years after the end of the recession. Those people who were hit especially hard during the recession – the less educated, the young, single families and people of color – are still living with high unemployment.

State policymakers have little influence over national economic trends, but Minnesota can take steps to narrow gaps in unemployment rates. Decisions made in the 2013 Legislative Session to make college more affordable are one step forward to ensure that more Minnesotans gain skills to compete in the workforce. State economic development efforts should also include a focus on the people most left behind in the recovery and make sure they have opportunities to succeed.

By Clark Goldenrod

[1] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, 2013.

[2] Data in this brief reflect Minnesota Budget Project analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. Figures by quarter are rolling averages. Individuals are defined as unemployed if they meet three criteria: they do not have a job, have actively looked for a job in the past four weeks and are currently available to work.

[3] Urban Institute, Unemployment From a Child’s Perspective, March 2013.

[4] Urban Institute, Testimony at the Meeting of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, April 2006.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2011.