The economic recovery has taken hold in Minnesota. Our state has recovered the jobs lost from the recession, and our unemployment rate is one of the lowest in the nation. But these figures disguise the fact that many Minnesota workers are not sharing in the state’s economic growth. Since Minnesota’s economic strength depends on more Minnesotans successfully participating in the workforce, making opportunity available to all should be a priority.

The most recent data that allows for a more detailed look at how Minnesotans are faring in the labor market show some troubling trends. In the fall of 2015, the same kinds of workers that suffered the highest levels of unemployment during the recession – the less educated, the young, single parents and people of color – still face higher unemployment rates.[1] Recently, unemployment rose slightly among single parents. On the positive side, unemployment fell for young and less educated Minnesotans and Minnesotans of color, even though they still face higher unemployment than older, more educated and white Minnesotans.

The state’s unemployment rate was 3.6 percent in September 2015. But that still means that more than 109,000 Minnesotans were looking for work.[2] This figure understates the number of Minnesotans who could use a good job. Official unemployment numbers only reflect workers actively looking for work and do not include discouraged workers who have left the labor force. Unemployment, even at lower rates, has consequences that are felt by the entire state. Minnesotans who are out of work are likely spending less, which reduces consumer spending – an important engine of economic growth. And extended periods of unemployment can force families to tap into savings meant for education or retirement, and cut back on essentials like health care or food.

Policymakers can take steps so that more Minnesotans are able to find and keep the jobs they need to support themselves and their families. These include expanding access to affordable child care and paid sick time, and supporting workers through the Working Family Credit.

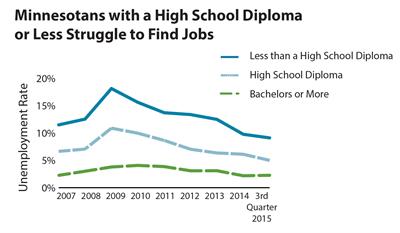

Minnesotans with Less Education Struggle in the Job Market

While the gap in unemployment rates between college graduates and those with a high school degree or less is narrowing, Minnesotans with lower levels of education still find it more difficult to get a job.

- Minnesotans without a high school diploma are four times more likely to be unemployed as those with a college degree. Over 9.0 percent of Minnesotans without a high school education were unemployed.

- For those with a high school diploma, the unemployment rate was 5.0 percent, over twice as high as the unemployment rate for those with a college degree.

- The unemployment rate for college graduates was 2.3 percent. This group weathered the recession far better than the others, and continues to experience very low unemployment.

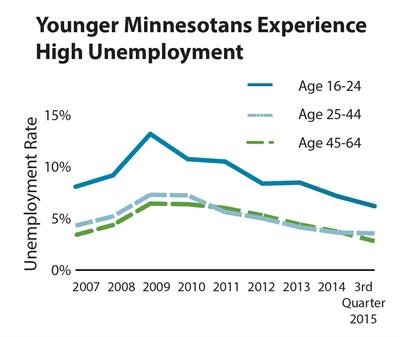

Younger Minnesotans Experience Higher Unemployment

Young Minnesotans are more likely than other age groups to be unemployed, which can be a significant setback at a critical time for getting started in their careers and may harm their future earnings. While unemployment among young adults ages 16 to 24 has declined substantially since the recession ended, they are still struggling in the job market.

- Young Minnesotans experienced unemployment rates as high as 13.2 percent during the recession. While unemployment for this group has decreased considerably, it was still 6.2 percent.

- Other age groups saw a less dramatic increase in unemployment during the recession, and unemployment rates are falling back to what they were before the recession. For 25- to 44-year-olds, the unemployment rate fell to 3.6 percent in the third quarter of 2015; and for 45- to 64-year-olds, the rate was 2.8 percent.

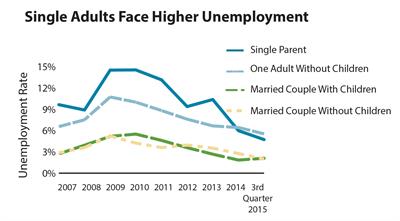

Single Parents are Struggling in Minnesota’s Economic Recovery

Households headed by a single adult experience more difficulty in Minnesota’s job market than married couples. Prolonged unemployment can also be harmful to children, with the loss of wages making it difficult for parents to provide nutritious meals and a safe environment, and parental stress causing greater tension in the home.[3]

A household headed by a single adult is particularly vulnerable after losing a job, since there isn’t a second income earner to help weather a stretch of unemployment.

- Single parents experienced very high unemployment rates during the recession. Their unemployment rate has since dropped; however, in the third quarter of 2015, 4.7 percent of single parents in the workforce were looking for work.

- Single adults without children also face high levels of unemployment. In the third quarter of 2015, 5.5 percent of single adults without children were seeking employment.

- Married couples – with and without children – have seen lower levels of unemployment for the past few years, never going above 6 percent even during the recession.[4] In the third quarter of 2015, unemployment among married couples without children was 2.0 percent, and for couples with children, it was 2.1 percent.

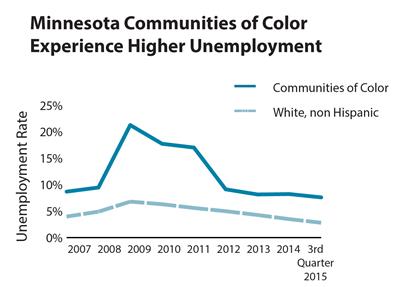

Minnesota’s Communities of Color Experience Higher Unemployment

Unemployment among people of color in Minnesota has improved since the recession, but still remains much higher than for white Minnesotans.[5]

This disparity likely reflects many of the other unemployment gaps discussed in this paper, since people of color are more likely to be young or have lower education levels, but also reflects discrimination in the labor market.[6]

- Unemployment among persons of color is now below pre-recession levels. However, it is almost 5 percentage points higher than the rate for white Minnesotans.

- Some communities experience much higher unemployment. For example, the unemployment rate in 2014 was about 13 percent for Native Americans and black Minnesotans.[7]

Policymakers Can Support Minnesota’s Workers to Narrow Employment Gaps

While the economic recovery is narrowing the gaps in unemployment rates, Minnesota policymakers should continue to do their part so that more Minnesotans are able to get and keep good jobs. Policy changes currently on the table include expanding access to affordable child care and earned sick time, and expanding the Working Family Tax Credit.

Affordable child care is important for parents to succeed in the workplace and for employers to have the reliable workers they need. But over 7,000 families are on the waiting list for Basic Sliding Fee Child Care Assistance to bring down the cost of care.[8] In addition to boosting funding for Basic Sliding Fee, enacting a targeted increase in the Child and Dependent Tax Care Credit would support the work efforts of thousands of lower-income Minnesota parents.

By expanding access to earned sick leave, policymakers can ensure more Minnesota workers keep their jobs when illness strikes. Currently, 1.1 million workers risk losing their jobs if they take time off when they or a family member is sick. Those workers who face the highest levels of unemployment are also often the most likely to lack earned sick time, including 60 percent of Hispanic workers and 47 percent of black workers in Minnesota.[9]

Another way policymakers can help Minnesotans succeed in the workplace is through expanding the Working Family Credit. This tax credit is based on a household’s earnings and family size, and can only be claimed by people who work. Policymakers are currently considering proposals to strengthen the pro-work impact of the Working Family Credit, including by strengthening it for younger workers and workers without dependent children – some of the groups who face the highest levels of unemployment. For both families and childless workers, an expanded Working Family Credit can help them stay in the labor market.

While Minnesota’s overall economic health is improving, the recovery is uneven and too many Minnesotans are not able to participate fully, which is a damper on our economic growth as a state. Taking policy actions so that more Minnesotans can get and keep good jobs is a smart investment in our future.

By Clark Biegler

[1] Data in this brief reflect Minnesota Budget Project analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey. Figures by quarter are rolling averages.

[2] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, 2015.

[3] Urban Institute, Unemployment from a Child’s Perspective, March 2013.

[4] For this analysis, a married couple is defined as experiencing unemployment if at least one of them is in the workforce and unemployed.

[5] For this analysis, communities of color are defined as individuals other than white non-Hispanic, including Hispanic, Black, American Indian, and Asian Minnesotans. These racial and ethnic communities were consolidated for data analysis purposes, although the unemployment experiences among these communities vary.

[6] Urban Institute, Testimony at the Meeting of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, April 2006.

[7] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2014.

[8] Minnesota Department of Human Services, Number of Families on the Basic Sliding Fee Waiting List, February 2016.

[9] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Access to Paid Sick Time in Minnesota, September 2014.